By Neenah Payne

By Neenah Payne

If America and Europe want to fight endless bankrupting wars, its best to glorify Western history – starting with Greece and Rome – and ignore the major contributions of ancient Egypt, China, India, Muslims, and Native America. However, if we want to create a rich world of peace and collaboration, the stated goal of the United Nations, it’s important to understand the real history of the world now.

After Venetian merchant Marco Polo (1254 –1324) traveled the Silk Road to China from 1271-1295, his The Travels of Marco Polo enthralled Europe with tales of the wealth of the East. The book was one of the most influential in human history. It tantalized Europe with tales of China’s immense wealth and advanced civilization. In 850 AD, China had invented paper – which made Marco Polo’s book possible. Favorite commodities from Asia included silk, jade, porcelain (“fine China”), tea, and spices. It is hard to overstate the importance of the Silk Road in history. The exchange of information gave rise to new technologies and innovations that changed the world and affect us today.

Amazon Description

Marco Polo was the original, trailblazing tourist. He was born into a wealthy Venetian merchant family in 1254 and at the age of 17 he embarked on an epic journey to Asia, as one of the first westerners to ever visit China. When he returned 24 years later, he recorded his extensive travels in a book – publishing possibly the first travel guide ever – and introducing Europeans to Central Asia and China. Marco Polo’s travels have since inspired countless adventurers to set off and see the world. Allegedly, Christopher Columbus set off across the Atlantic with a copy of Marco Polo’s original book!

Marco Polo was the most famous traveller of his time. His voyages began in 1271 with a visit to China, after which he served the Kubilai Khan on numerous diplomatic missions.

On his return to the West, he was made a prisoner of war and met Rustichello of Pisa, with whom he collaborated on this book. The accounts of his travels provide a fascinating glimpse of the different societies he encountered: their religions, customs, ceremonies, and way of life; on the spices and silks of the East; on precious gems, exotic vegetation and wild beasts.

He tells the story of the holy shoemaker, the wicked caliph, and the three kings, among a great many others, evoking a remote and long-vanished world with colour and immediacy. He found himself traversing the most exotic lands-from the dazzling Mongol empire to Tibet and Burma. This fascinating chronicle still serves as the most vivid depiction of the mysterious East in the Middle Ages.

Swedish Explorer Sven Hadin wrote in The Silk Road, “It can be said without exaggeration that this traffic artery through the whole of the old world is the longest, and from a cultural-historical standpoint, the most significant connecting link between peoples and continents that has ever existed on Earth.”

Christopher Columbus sailed West to find a safer route to the East than the dangerous Silk Road from Italy to China and died thinking he had reached India. That’s why the indigenous peoples of the Western hemisphere are mistakenly called “Indians” today.

The Silk Roads: A New History of the World

Amazon Description

INTERNATIONAL BESTSELLER

Far more than a history of the Silk Roads, this book is truly a revelatory new history of the world, promising to destabilize notions of where we come from and where we are headed next. “A rare book that makes you question your assumptions about the world.” — The Wall Street Journal.

From the Middle East and its political instability to China and its economic rise, the vast region stretching eastward from the Balkans across the steppe and South Asia has been thrust into the global spotlight in recent years. Frankopan teaches us that to understand what is at stake for the cities and nations built on these intricate trade routes, we must first understand their astounding pasts.

Frankopan realigns our understanding of the world, pointing us eastward. It was on the Silk Roads that East and West first encountered each other through trade and conquest, leading to the spread of ideas, cultures, and religions. From the rise and fall of empires to the spread of Buddhism and the advent of Christianity and Islam, right up to the great wars of the twentieth century—this book shows how the fate of the West has always been inextricably linked to the East.

Also available: The New Silk Roads, a timely exploration of the dramatic and profound changes our world is undergoing right now—as seen from the perspective of the rising powers of the East.

The New Silk Roads: The New Asia and the Remaking of the World Order

Amazon Description

From the bestselling author of The Silk Roads comes an updated, timely, and visionary book about the dramatic and profound changes our world is undergoing right now—as seen from the perspective of the rising powers of the East. “All roads used to lead to Rome. Today they lead to Beijing.” So argues Peter Frankopan in this revelatory new book.

In the age of Brexit and Trump, the West is buffeted by the tides of isolationism and fragmentation. Yet to the East, this is a moment of optimism as a new network of relationships takes shape along the ancient trade routes. In The New Silk Roads, Peter Frankopan takes us on an eye-opening journey through the region, from China’s breathtaking infrastructure investments to the flood of trade deals among Central Asian republics to the growing rapprochement between Turkey and Russia. This important book asks us to put aside our preconceptions and see the world from a new—and ultimately hopeful—perspective.

The New Silk Road: Belt & Road Initiative (BRI)

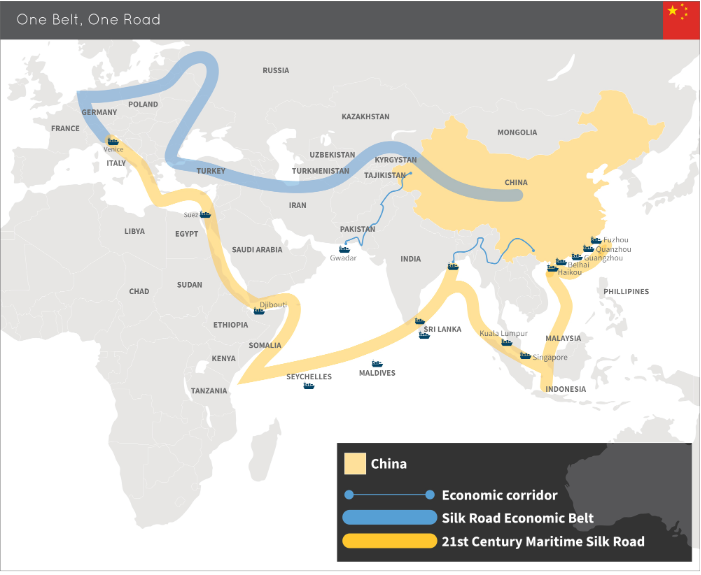

China’s Expanding New World Order! explains that in 2013, President Xi Jinping of China announced the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) aka “New Silk Road” in one of the most significant speeches in China’s recent history. It is the largest infrastructure project since the Marshall Plan. The stated goal of the BRI is to create a new infrastructure for world trade between 65 countries.

President Xi Jinping has overseen the construction of the largest rollout of high-speed trains, the lifting of millions of Chinese out of poverty, and the establishment of China as the world’s fastest-growing economy, but his plans extend around the globe in multiple ways.

Xi’s vision in not just for China – but for much of Europe, the Middle East, Asia, and Africa! It includes participation in the BRICS nations and his Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) aka “The New Silk Road” that will link 65 nations throughout Asia, Africa, and Europe. China’s investment in the infrastructure of many of the 55 African nations is reviving that continent and winning friends for China. In a win-win arrangement, China is gaining access to the mineral resources it needs for industrialization while building roads, highways, schools, universities, hospitals, airports, wells, and manufacturing centers for Africa. The West has much to learn from China’s way of dealing with Africa.

Rise of China: Back To The Future

The Age of Discovery began when Columbus stumbled on the Western Hemisphere. With colonial expansion, Europe developed a trade monopoly. By the mid-19th century, the introduction of the steam engine led to a transition in Europe from a hand-crafted economy to the Industrial Revolution based on machine-powered mass production.

As Europe embarked on widespread colonization, the caravans on the Silk Road began to disappear and, after a millennium of prosperity, the Silk Road went into decline. Europe became enriched through its colonization of the Americas, Australia, Asia, as well as its enslavement of Africans and colonization of Africa after the Berlin Conference of 1884-1895.

One Belt One Road Documentary Episode One: Common Fate reports that President Xi said in his speech proposing the new Silk Road that the old Silk Road was the center of trade, knowledge, and civilization. China introduced not only silk to Europe, but paper and printing, spices, gun powder/fireworks, the compass, and medicines. Constantinople (Istanbul), Venice, and other cities sprang up and prospered on the Silk Road.

China also introduced the toothbrush, compass, moveable type printing, paper money/bank notes, the mechanical clock, porcelain (fine “China”), matches, seismograph, oil drilling, rockets, earthquake detectors, the suspension bridge, paper (boxes, wrapping paper, Kleenex, toilet paper), rudder, deep drilling wheelbarrow, adjustable wrench, lacquer, the blast furnace, stirrups, the crossbow, hang gliders, the abacus, row crop farming, moldboard plows, kites, iron smelting, the seed drill, umbrellas, the decimal system, bronze, noodles, and tea.

When China was smelting iron, Europe lagged far behind. China’s capital city was the world’s largest, seven times bigger than Constantinople. By the 11th century, China had 11 cities with a population of 100,000 while the largest city in Christian Europe had yet to reach 20,000. Chinese innovations like the magnetic compass were reaching the West via the Silk Road and were changing the world.

The West was dominant from the 16th to the mid-20th century. However, after WWII, mass liberation movements swept across Asia and Africa. The new countries that emerged faced a common challenge – the need for development. The first Asian-African Conference was held in 1955 in Bandung, Indonesia which fostered unity among the developing nations. It was the origin of “South-South” cooperation.

A broad consensus developed that there was a need for a new Silk Road to unite humanity in a project for exchange of information. The Silk Road reached its lowest ebb in the late 19th century. With the establishment of the People’s Republic of China by Mao Zedong in 1949, China’s colonial and feudal period came to an end. The adoption of the reform and opening policy in the 1970’s boosted its economic power. In 1978, China was the world’s 10th largest economy in terms of GDP. By 2016, China had the second largest economy after the US. By 2019, the US GDP was $21.44 trillion while China’s GDP had grown to $27.31 trillion.

In the 21st century, China is building an impressive network for high-speed bullet trains. China’s investment in developing its infrastructure and that of Africa is inspiring the world. The West is increasingly being left behind now as America continues the endless expensive War on Terror and fails to develop at home.

How The Silk Road Made The World

Episode One: War

How the Silk Road Made the World | Episode One: War 5/1/23

The Silk Road is one of humanity’s greatest enterprises. For thousands of years across the vastness of Eurasia, a trade route linking east and west has deeply influenced history. Silk Road trade has helped to build and break empires, has fed revolutions and has profoundly affected civilisations. This episode explores how the Silk Road influenced conflict, from cavalry warfare to gunpowder.

The video explains how the Chinese invented gunpowder. When Chinese and Mongols attacked Russia and Poland with gunpowder in the 13th century, this invention changed European history. In 1346 CE, during The Battle of Crecy, the English used guns for the first time in fighting the French. That was the beginning of the end for the medieval knight. Within two centuries, Europeans would use guns to dominate the world – creating empires that evolved into today’s global trade which binds people together by commerce instead of the gun.

The video explains that the Roman Empire seemed unstoppable 2,000 years ago. With Europe’s finest foot soldiers, it had conquered much of Europe. In 53 BC, on its way to conquer the East, when the Roman army of 40,000 faced the Parthian army of 10,000, Roman victory seemed inevitable. However, the Parthians were on horseback and killed or captured some 30,000 Romans. Parthian losses were minor. It was one of Rome’s worst military defeats.

Horses had been domesticated in Kazakstan and Russia by 3,500 BC or even 4,500 BC. In about 1,600 BC, Egyptians were using horse-driven chariots. Horses were not used as organized cavalry until about 900 BC. The video explains the technological revolutions that created socketed arrow heads in the West, recurved composite bows in the East, and cavalries in the South. When the three met around 900 BC, calvaries became a really deadly military forces and revolutionized warfare. Chinese cavalries used an additional lethal weapon, the crossbow. The stirrup was widespread by the 8th century CE and created a new era. Plate armor for the cavalry came later.

Roman gold traveled East on the Silk Road in exchange for Chinese silks. When the Huns attacked Rome in the 4th century CE, European barbarians like the Goths and Visigoths sought refuge in Roman territory – and never left. The Roman Empire was plunged into chaos as barbarian tribes rebelled against Rome.

In the 13th century, the Mongols conquered as far west as Poland. The “Pax Mongolica” made the Silk Road safe to travel and Europeans began traveling East as never before. The Italian cities of Venice and Genoa grew wealthy.

Episode Two: Light From Darkness

The Silk Road: Episode 2 – Light From Darkness 7/12/23

How the Silk Road Made the World: Episode2 – Light From Darkness explores how disease and life spread along the Silk Road to change the world.

The video explains how the Mongols spread the Black Death to Europe starting in 1346 on the shores of the Black Sea. By 1350, it was killing people all across Europe as far away as Greenland. In just a decade, the Black Death killed at least 25 million Europeans, 30% of Europe’s population. Scientists believe the plague was transmitted to humans by infected fleas living on rats. It spread across Eurasia by hitching a ride on ships and caravans along trade routes. How the Black Death Spread Along the Silk Road.

However, as the Black Plague decimated Europe’s workforce, opportunities increased and wages went up due to the shortage of workers. Over the next 200 years, labor-saving devices like the spinning wheel were invented. As more land was available for farmers, the European middle class was born. Women could work as scribes and in other jobs formerly reserved for men.

The video also explains that the spread of millet, wheat, and barley between China and Europe allowed farmers to grow two crops each season instead of one – freeing some people from farming. In the late Middle Ages, spices like cinnamon, pepper, and clovers were highly valued. Venetian merchants dominated the spice trade and Venice became fabulously wealthy. European merchants were cut off from the Silk Road when Turks conquered Constantinople in 1453 with cannon – using gunpowder invented in China. Europe needed new routes to the wealth of the East – which is what inspired Columbus to find a Western route.

Episode Three: Revolutions

How The Silk Road has fed Revolutions 7/19/23

How the Silk Road Made the World: Episode Three – Revolutions delves into events and objects that were central to the Age of Revolutions.

The video explains how the Chinese invented paper around 100 CE or earlier. They first used paper as a wrapping material and later for writing. By the early centuries of the Common Era, the Chinese were using paper in all the ways we do now including as facial tissue and toilet paper. The Chinese took the knowledge of paper-making to Japan, Korea, and Vietnam.

In the 8th century, Arabs learned about paper-making from the Chinese. A parchment book required 200 animal skins and cost a fortune. Paper was less expensive and more versatile than parchment or Egyptian papyrus. The Abbasid Caliphate founded around 750 CE in Bagdad ruled the greatest empire of its day and established The House of Wisdom. The availability of cheap paper made possible one of humanity’s greatest literary eras. Bagdad became the center of learning where books about science, geography, astronomy, medicine, mathematics, etc. were written or translated from many languages into Arabic and Latin.

During the Middle Ages, an intellectual Golden Age flowered in Arab Spain. Muslim, Jewish, and Christian scholars collaborated. Libraries in the Muslim world used paper while libraries in Europe used parchment. The library of the Cordovan caliphate in Spain reportedly had 400,000 books in 960 or 970– more than 100 times the number of books in the largest university library in Chrisitan Europe several centuries later.

By the late Middle Ages, Italian cities like Fabriano and Amalfi had become Europe’s leading paper manufacturers, shipping tons of paper to businessmen throughout Europe. This mass production of paper was changing Europe in other profound ways. The art of drawing probably developed in Italy in the 15th century because of access to paper. Michaelangelo made drawings of his paintings on paper that would have been too expensive on parchment.

China developed the printing press in the ninth century. The world’s oldest printed book was printed in 868 CE. Four hundred years later, around 1300, ancient wood block printing had traveled the Silk Road to the West. By then, China had developed a more efficient way of printing – the earliest known use of moveable type. However, it was a difficult system since Chinese has thousands of characters.

In 1440, German goldsmith Johannes Gutenberg came up with a new way of printing. He began with a screw press which had been invented by the Romans to make wine and used in Gutenberg’s time to make wood block prints. He made his own moveable type by punching letters out of metal and cast them using a hand mold he invented. He devised a system to easily compose lines of type in trays and invented an oil-based printing ink that transferred easily to metal type. When Gutenberg printed the first 180 Bibles, he used paper from China.

Gutenberg’s printing press was much faster and more efficient than Chinese printing techniques because the Latin alphabet has just 26 letters. The video says, “If ever a new technology re-wrote human history, it was Gutenberg’s printing press!” Within a few years, millions of Europeans were reading the Bible and other best-selling books translated into their languages – something we take for granted now. However, in 15th century Europe, it was revolutionary! There was an enormous demand for printed texts. Paper and the printing press had achieved something never done before. They had democratized knowledge.

For thousands of years, monks in monasteries had copied manuscripts by hand in a top-down system. The pope could distribute information, but people at the bottom could not. The printing press created a new middle class of merchants in Europe and a whole new market where the written word was in very high demand.

Europe’s ability to mass produce books would soon have enormous consequences. In Germany, a firebrand monk named Martin Luther wrote a list of 95 proposals for reforming what he denounced as the corrupt practices of the Catholic Church. Thanks to paper and the printing press, his ideas spread like wildfire across Germany and Switzerland and began the Protestant Reformation – a spiritual revolt that ended Catholicism’s thousand-year monopoly of the European soul.

How The Silk Road has fed Revolutions adds that other best-selling books helped Cristobal Colon, an Italian living in Spain, realize his dream. He was deeply disturbed that the holy cities of Christendom had fallen under the rule of the Ottoman Turks. Colon drew up plans for a new Crusade to liberate Jerusalem. To fund it, he decided to travel to Asia to get spices and other luxury goods he could sell for a large profit back home.

However, the Ottoman Empire had blocked Europeans from the Silk Road. So, Colon needed to find a new route to Asia. The Travels of Marco Polo and Geography by the ancient Greek author Ptolemy convinced him he could find Asia by sailing West across the Atlantic. When he landed in the Americas in 1492, Colon (known to history as Christopher Columbus) was sure he had found India.

Europeans used the wealth confiscated from the Western hemisphere to pay for two luxuries: porcelain and tea. China had been making porcelain since the ninth century. For the next 300 years, Europe became obsessed with “fine China” as a status symbol. Porcelain was indispensable for consuming tea –another Chinese trade good craved by Europeans.

China had been exporting tea to the Middle East since the ninth century – but not to Europe. The Portuguese began trading for it in the 16the century after they sailed around Africa to reach China.

In 1657, a London merchant sold the first tea in Britain. By 1700, tea-drinking had become a British obsession — heavily promoted by the British East India Company which traded textiles to China and needed a profitable luxury good to bring back to Britain.

In the 17th century, when Europe began trading American food crops like corn, potatoes, sweet potatoes, peanuts, pineapples, chiles, and tomatoes to China, China’s population grew until China became the world’s most populous nation.

Mattio Richi, an Italian Jesuit, arrived in China in 1582 and spent the rest of his life there as a Catholic missionary. He learned to speak, read, and write Chinese. Richi converted a prominent Chinese astronomer and mathematician to Catholicism. Richi asked his superiors in Europe to send smart missionaries to China. From the 16th to the 19th century, nearly 1,000 missionaries worked in China – sending back translated Chinese classics. That gave Europe its first in-depth knowledge of Chinese civilization and China its first in-depth knowledge of the West.

King Louis XIV of France sent French Jesuits to the mission in China. Chinese emperors appointed Jesuits to important government positions. For more than 100 years, Jesuit astronomers directed the imperial astronomical bureau. A German Jesuit helped create a new Chinese calendar that predicted solar and lunar eclipses with more accuracy. He also introduced his Chinese colleagues to a new European invention, the telescope.

In 1756,Voltaire argued that China was the paragon of enlightened monarchy because it was ruled with reason by educated and virtuous intellectuals with scholarly accomplishments and merits rather than by hereditary right. He challenged the notion that the Christian European world was the beginning and the center of civilization. In Voltaire’s time, European were fighting hereditary kings for the right to rule themselves. By 1800, political revolutions in Britain, America, and France had ended centuries of absolute monarchy.

New technologies like the mechanical loom and the steam engine with the rise of industrial capitalism were connecting the far corners of the world. Gunpowder, an ancient Chinese invention that had spread Westward centuries earlier and had made modern warfare possible, was being used in 16th century France to blast a mine tunnel in the rock in mineral-rich areas like France’s Vosges Mountain. The gold rush happened in the US during the 19th century. It Europe, it was the “silver rush” in the Vosqes in the 16h century.

By the beginning of the 19th century, gunpowder allowed mining to evolve from laborious hand digging to a modern enterprise to finance Europe’s growing industrial economy. Across the Atlantic, gunpowder was about to help the US unlock its vast economic potential. On July 4, 1817, crews in New York state began digging the Erie Canal, a nearly 600-kilometer shipping channel designed to connect the Great Lakes with the Hudson River and the Atlantic Ocean so towns on America’s frontier could ship and sell their products worldwide. Starting in 1812, gunpowder was used to cut through dolomite in two years to build the canal. By the end of 1825, the Erie Canal was officially open for business.

Before roads and railroads had penetrated the North American wilderness, the Erie Canal made possible the westward expansion of the young United States. The digging of the Erie Canal had another enormous consequence. It made New York City a world leader in maritime commerce and all the other businesses — like insurance, financing, and grain exchange – that go with maritime financing. They all happened in New York because the Erie Canal brought produce from the interior of the continent to the Atlantic via the New York harbor.

By the 20th century, New York had become the prototype of the megacity. Spawned and sustained by global trade, the megacity transcends its national roots and becomes a world city encompassing human diversity. New York’s evolution was the ultimate expression of forces that had been at work for thousands of years – set in motion and sustained by the East-West commerce of the Silk Road, a path through history that didn’t just link human beings together, but shaped their fates.

The video says:

The Silk Road was like a ray of light that opened our eyes – East and West – to intangible ideas, to beautiful things, to beautiful thoughts. Today, the ancient tale of the Silk Road seems like story of an exotic past – but, in fact, it is just as much a story of the future.

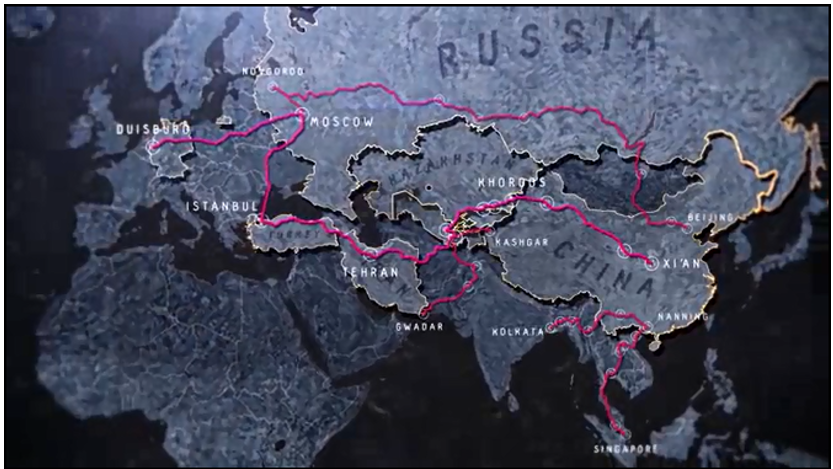

Two or three times a week, a train departs from a Chinese city loaded with Chinese manufactured consumer goods and its route takes it across six countries in Central Asia and Eastern Europe. It takes 18 to 20 days to reach one of several destinations in Western Europe over distances of some 12,000 to 13,000 kilometers. Loaded up with European-manufactured goods, it returns to China.

The EU railway is pioneering the return of the Silk Road. On May 14, 2017, China hosted a conference in Beijing to promote its One Belt One Road initiative. Attending were delegates from around the world including the heads of the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, and the United Nations, and nearly 30 heads of state. Known as OBOR, One Belt, One Road plans to build a $1 trillion transport network that will connect some 60 countries, two thirds of the world’s population, and one third of the world’s GDP.

Inspired by the old Silk Road, it will re-establish the ancient trade routes over land and by sea, and it will also create a new Silk Road– in space. On August 1, 2027, China’s space craft released the nano satellite into orbit Silk Road 101 Qusat into orbit. It is a pathfinder for a constellation of around 30 satellites operating across a variety of wavelengths. These satellites will help build an efficient and reliable satellite navigation system that will provide mapping and navigation services and remote sensing technologies to all the cities of Western China and to all the countries along the new Silk Road.

Zhou Jianping, General Engineer of China Manned Space Engineering pointed out,

Going into space can offer a superior way of connection for global communications. The communications satellite and Earth observation are both typical examples. In 2020, we will complete basic construction of the space station. After that, we will start to operate the space station and we will constantly extend its application as needed.

Yang Liwei, Director of China Manned Space Engineering Office explained:

We hope through our space station, we will be able to promote the development of space for humankind and to be a responsible nation in space. After the space station is launched, I believe more countries will participate in its development as well as experiments and scientific achievement.

China’s quest to become a space power runs through Silk Road city

Zhou Jianping added:

All countries can share in the achievements through this initiative, advancing the building of a human community with a share civilization. The unique advantages of space will definitely play a part in the construction of the Belt and Road Initiative.

Neenah Payne writes for Activist Post

Become a Patron!

Or support us at SubscribeStar

Donate cryptocurrency HERE

Subscribe to Activist Post for truth, peace, and freedom news. Follow us on SoMee, Telegram, HIVE, Minds, MeWe, Twitter – X, Gab, and What Really Happened.

Provide, Protect and Profit from what’s coming! Get a free issue of Counter Markets today.

Be the first to comment on "The Amazing Silk Road Returns!"