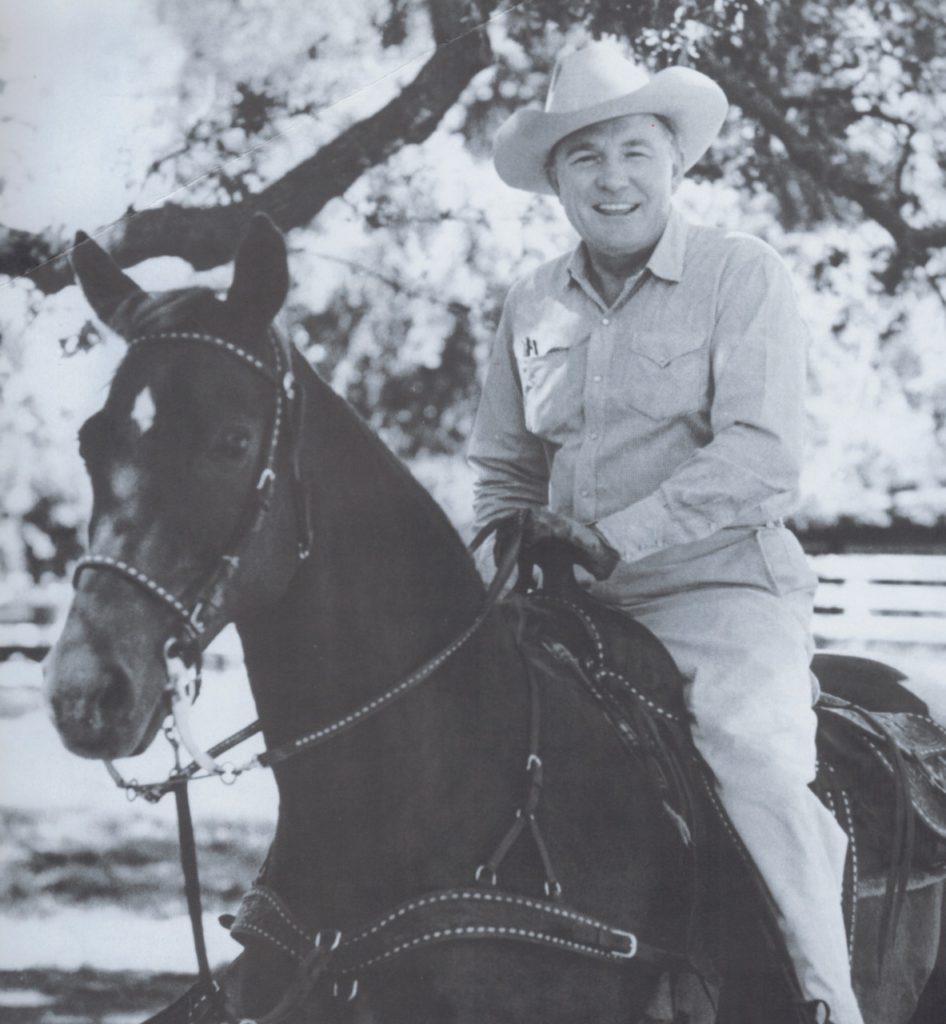

An aerospace executive by the name of Charles ‘Tex’ Thornton (1913-1981) appears to have been central to the historical development of today’s New Manhattan Project. He worked on many technologies germane to the project and worked for many organizations and with many individuals implicated in the project. His crowning achievement was a company called Litton Industries which worked in many areas closely connected to the New Manhattan Project. This article tells his story. For a full explanation of the New Manhattan Project, please refer to the new, greatly revised and expanded second edition of the author’s book Chemtrails Exposed: A New Manhattan Project now available exclusively at Amazon.

In 1934, at the age of 21, Tex Thornton went to Washington to find a job with the federal government. After all, 1934 was during the depths of the Great Depression and federal government work under FDR’s administration was about the only sector of the economy that was booming. He initially found a job in the Agricultural Adjustment Administration, but later transferred to the War Department in 1941.

It was around this time that Thornton first met Assistant Secretary of War Robert A. Lovett (1895-1986). Thornton had displayed an outstanding aptitude in the language of statistics and originally contacted Lovett on the recommendation of a university economics professor who was a common friend of both men. Throughout much of Thornton’s career, Lovett would prove to be his most valuable ally. Both men were from Texas, but from opposite ends of the socio-economic spectrum. While Thornton was from humble beginnings, Lovett was a creature of the old money establishment. Lovett was a member of the Skull & Bones secret society as well as a partner at Brown Brothers Harriman. Lovett saw Thornton as someone who could help him in his effort to massively expand American air war capabilities. In early March of 1941, Lovett arranged for Thornton to be inserted into the plans division of the Army Air Force (AAF), putting Thornton in charge of a small group of men; mainly from the National Guard.

The Whiz Kids

The catalyst for expanding the Army Air Force came with the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and America’s official entry into WWII. By March of 1942, General Henry ‘Hap’ Arnold (1886-1950) had announced a major reorganization of AAF headquarters. As part of this reorganization, Tex was made the head of a relatively insignificant group called Statistical Control operating under Colonel Byron E. Gates and his office of Management Control. In order to carry out his expansion plans, Secretary of War Lovett subsequently suggested to Tex that he go to the Harvard Business School to persuade the dean into creating a program to train an elite group of officers in the area of statistical management. In April of 1942 Thornton did so.

At the Harvard Business School, Thornton met with Dean Wallace B. Donham (1877-1954) who promptly called upon a group of the youngest members of his faculty. The dozen or so assistant professors assembled to receive Thornton all had draft numbers. Some of them had draft numbers so low that they might be sucked into the war at any moment. The future Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara (1916-2009) was among this group. Thornton made a presentation explaining how he had been sent to recruit men who could help reorganize the AAF. Thornton convinced them to come with him to Washington to design his proposed Harvard Business School Stat Control courses. Mere hours after meeting with Tex, the group of young professors boarded a train bound for Washington. Six weeks later, more than one hundred students reported to Stat Scho ol’s first session.

The students Tex recruited were first required to spend six weeks at the Army Air Forces’ Officer Candidate School in Miami where they were given traditional military training with an emphasis on their job at hand. Half way through this training, Tex arrived to choose the best and brightest who could then complete their military training at Harvard. The Stat School took up quarters at Harvard’s Mellon Hall as the newly mobilized Harvard Business School took on the appearance of a military academy. Within a year, Harvard had suspended all civilian instruction.

The graduates of Harvard’s Stat School were dispatched to U.S. military bases around the country and around the world in order to assess and keep track of AAF inventories. The most important of Stat Control’s operations were those at Patterson Field in Dayton, Ohio which employed the world’s largest installation of International Business Machines (IBM) computer equipment. Every night, Stat Control reports from around the country would come in via teletype and be compiled. Every morning a report would be produced showing local inventories of AAF resources including airplanes, personnel, parts, fuel, ordnance, and more. Production of these reports, delivered to AAF generals, was the purpose of Stat Control and it was a smashing success. The success of this program earned the Stat Control members the moniker of ‘The Whiz Kids.’

Ford

Following the war, Thornton created brochures which he sent to more than one hundred companies advertising himself and selected members of Stat Control for employment. He received at least 10 replies expressing interest from, among others, Arthur D. Little, Inc. But one of Tex’s group, George Moore got a hot tip. George’s father was friends with the treasurer of the Ford Motor Company; a man by the name of Burt J. Craig who informed George’s father that Henry Ford II (1917-1987) was looking for new executives. George told Tex and on Oct. 19, 1945, Tex sent a telegram to Henry II. The next day, Tex got a phone call from a functionary in Ford’s Washington office informing him that Henry was very much interested and wanted to meet with him in Dearborn, Michigan – the Ford Motor Company’s executive headquarters. Tex acceded and met with Ford who had already conferred with Assistant Secretary of War Lovett. After the brief meeting, Henry II hired Tex and all of his men. On January 29, 1946 the Whiz Kids arrived in Detroit to start their new life as executives at the Ford Motor Company.

Shortly after Thornton and his men arrived at Ford, Ernest R. Breech (1897-1978) was brought in as President. Breech had previously been the head of Bendix Aviation Corp. Thornton was henceforth required to report to Breech, not Henry II. Thornton was not happy with this situation and hence, Breech and Thornton were in constant competition for power.

Also following the war, Lovett returned to his position at Brown Brothers Harriman. Lovett’s next military assignment was as the under secretary to General George Marshall (1880-1959). After Thornton encountered more friction at Ford Motor between himself and another Ford executive by the name of Lewis Crusoe (1895-1973), Thornton jumped at Lovett’s suggestion that Tex come to Washington to work for him on a temporary special assignment. Lovett wanted Thornton to reorganize the Department of State. While on his leave from Ford, Thornton worked out of an office between Lovett’s and Marshall’s offices. During this time Thornton was kept abreast of the goings on at Ford by his fellow Whiz Kids.

Upon his return to Ford, Thornton continued to conflict with Crusoe and Breech. Thornton was acting like he was the boss when he wasn’t. Crusoe was grousing that Thornton’s ambition was way ahead of his ability. Thornton’s boss Breech had had enough. Breech simply called Thornton into his office and promptly fired him for insubordination. The leader of their group was no longer working at Ford and the original Whiz Kids had been officially broken up. It was decided that Bob McNamara would henceforth be the leader of the remaining Ford Whiz Kids.

Hughes

Shortly after Thornton’s firing, in early January of 1948, Thornton’s old wartime friend General Ira Eaker (1896-1987), who was then working at Hughes, asked that Thornton go to California to speak with Howard Hughes (1905-1976). Thornton followed Eaker’s suggestion. Hughes and Thornton soon met and Hughes ended up hiring Thornton in May, about 4 months after his firing at Ford.

On his first day at Hughes Tool Works, Thornton was given an assignment to work at a small, dysfunctional division of Hughes Tool in Culver City called Hughes Aircraft. Hughes wanted Thornton to study the operation and get back to him about how Thornton thought it should be run. Hughes Aircraft had been started in 1934 mainly to build private racing aircraft for Howard. At the time Thornton came in, Hughes Aircraft was still working on the gigantic Spruce Goose airplane. Hughes aircraft had some other disparate activities as well, such as the production of firearm ammunition accessories and television cabinets. Thornton’s direct superior at Hughes, a man by the name of Noah Dietrich (1889-1982), was suggesting that Hughes Aircraft should be shut down.

Despite the apparent air of dysfunction, at Hughes Aircraft Thornton found some brilliant scientists working on some extremely cutting edge technology. They were working on two air force studies: one was a fire control system involving radar and a gunsight cooperating with a computer, the other pertained to a guidance system for an air-to-air missile. The new, faster jet aircraft required these types of advanced fire control systems. Working on these two studies were two former Cal Tech classmates named Simon Ramo (1913-2016) and Dean Wooldridge (1913-2006). Ramo had previously been working at General Electric and Wooldridge at Bell Laboratories. Thornton was quite impressed with the work of Ramo, Wooldridge, and the other men working on these projects and he decided that Hughes Aircraft should terminate their other activities and concentrate solely on these guidance and fire control projects.

Dietrich didn’t like Thornton’s recommendations, though. At a meeting with Dietrich and Eaker, Thornton suggested that Hughes invest millions in a major expansion program into military electronics at Hughes Aircraft while Dietrich continued to assert that the whole operation should be scuttled. While Dietrich dug in his heels, Thornton’s friend Eaker went around Dietrich and lobbied Hughes to follow Thornton’s plan. Hughes ended up siding with Thornton and Eaker, and advanced the cash with the stipulation that Eaker be the liaison between Hughes Tool Works and Hughes Aircraft. Eaker then, with Thornton’s approval, recruited their mutual acquaintance, Lieutenant General Harold L. George (1893-1986) to be the general manager of Hughes Aircraft with Thornton as his assistant manager.

Thornton then went about building a new team at Hughes Aircraft. Thornton selected men from his Harvard Stat Control days to work at Hughes. Ramo and Wooldridge also called upon others to join them. In 1948 the new Hughes Aircraft got their first contract – a $8M dollar deal to build fire control systems for the Lockheed F-94 jet fighter aircraft. At the new Hughes Aircraft, Tex Thornton was learning a lot about electronics. He saw the immense potential of the field, not only for the military but for civilian life as well. He was becoming somewhat of a futurist.

During a visit to Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in September of 1948, Thornton’s acquaintance from the war, General Kenneth B. Wolfe (1896-1971), now the head of procurement for the Air Force, told Thornton about something called Project Bow Legs. As of the time of Thornton’s visit, Hughes had just scored the contract for Project Bow Legs. Project Bow Legs was all about what Thornton’s scientists at the new Hughes Aircraft were already working on: jet aircraft fire control. Thornton, ever the opportunistic salesman, immediately began selling Wolfe on the idea of greatly expanding Project Bow Legs. Wolfe had his doubts, but Thornton soon ran his ideas past Ramo and Wooldridge at Hughes Aircraft and came up with a planned schedule. He told Wolfe he could have a system produced in 11 months. It was game time for Thornton and Hughes Aircraft.

Thornton began recruiting top-level managers from every blue-chip defense contractor in the country including General Electric. Ramo and Wooldridge, once again, lured many more sharp scientists and technicians to Hughes Aircraft for the project. Thornton and Hughes met the deadline and, in the process, Hughes Aircraft had once again transformed itself. Hughes Aircraft was now the sole provider of jet aircraft fire control systems for the entire U.S. Air Force. Thornton and Hughes then captured a key contract to build the Air Force’s first radar guided air-to-air missile known as the Falcon. During this time, between the detonation of the first Soviet nuclear bomb in 1949 and the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950, Hughes Aircraft had all the business they could ever want. Hughes emerged with a virtual monopoly on all of the Air Force’s advanced electronics needs. Thornton’s Hughes Aircraft was another smashing success.

Dietrich resented Thornton’s success. He had never liked what Thornton was doing and to see him be so successful at it made him all the more resentful. Compounding the problem, even though Thornton had done tremendous work for Howard Hughes, it appears that, once again, a clash of the egos, this time between Hughes and Thornton, had soured their business relationship. These familiar frictions continued for some time until August 11, 1953 when Ramo, Wooldridge, and 19 other members of the scientific and engineering staff submitted to Howard Hughes a joint letter of resignation. Ramo and Wooldridge went on to form the Ramo-Wooldridge Corporation which eventually became TRW, Inc. Four days after the two lead scientists had submitted their letter of resignation, Thornton submitted his. Dietrich was left as the manager of Hughes Aircraft.

Before we move on, it should be noted that Hughes Aircraft has a couple of important connections to the New Manhattan Project. When Thornton became the boss there, he took over managerial control of the company from Pat ‘Welsbach Effect’ Hyland (1897-1989), who, at the time, became the number two man. The Welsbach effect is a physical phenomenon directly applicable to today’s New Manhattan Project. Hyland served as the head of Hughes Aircraft for many years. Also, the infamous “Stratospheric Welsbach Seeding for the Reduction of Global Warming” patent was assigned to Hughes Aircraft.

Litton Industries

Tex was looking for the next thing and he found it in a little company in San Carlos, CA called Litton Industries. Litton Industries was owned by an engineer named Charles V. Litton (1904-1972). Litton wanted to sell. For many years previously, Thornton and Hughes Aircraft had been buying Litton’s magnetron tubes for their fire control systems because Litton’s tubes were the best in the business. Tex had met Litton once before and was now considering the purchase of Litton Industries for the profitable core of a much larger future corporation. But to do this, he needed some money.

After shopping itself around quite a bit, Litton Industries was eventually acquired by Thornton with the assistance of Glen McDaniel, a Wall Street lawyer Thornton had met while working at Hughes Aircraft. Cash for the deal was supplied by Ransom Cook (1900-1986) of the American Trust Company in the form of a $300K loan while Lehman Brothers financed even more of the deal by selling some of Litton’s stock and bonds, raising $1.5M. Tex, ever the master negotiator, ended up with roughly 80% of the company. In late 1953, Tex finally had his own business.

Not long after Litton’s founding, Joe Thomas of Lehman Brothers and Carl Spaatz (1891-1974), who had served as the Air Force’s first Chief of Staff joined Litton’s board of directors. Whiz Kids J. Edward Lundy, Arjay Miller, and James Wright all went on to serve on Litton’s board of directors as well.

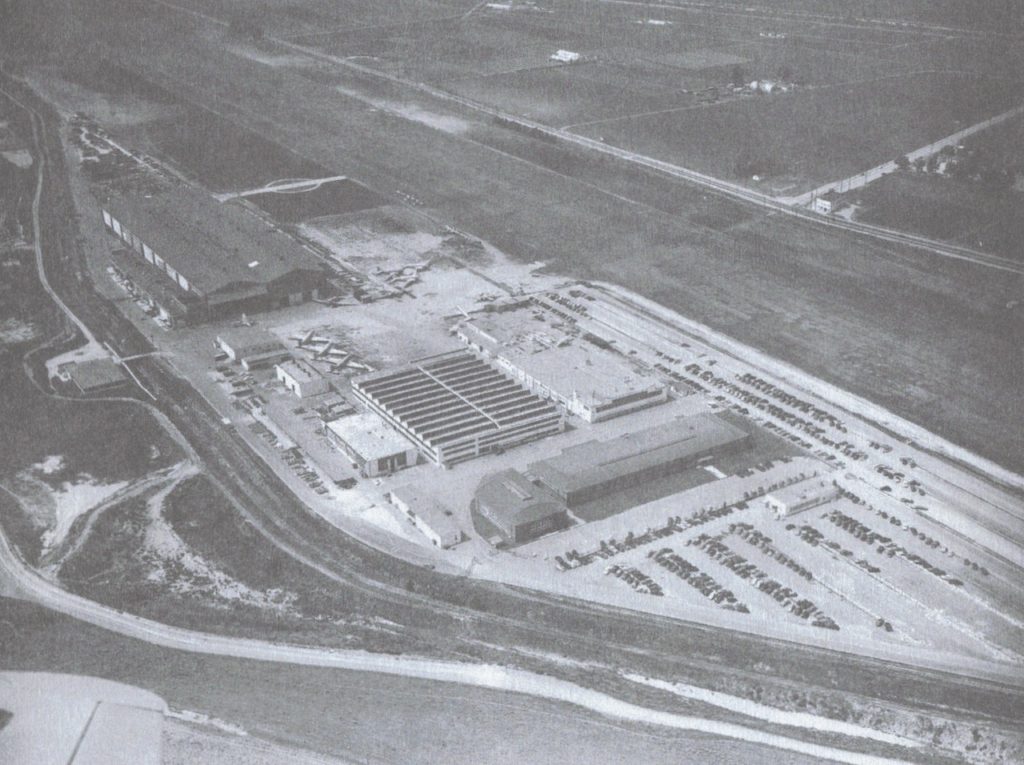

In early 1954, Thornton established the new Litton Industries headquarters in Beverly Hills, CA. Drawing upon his multitudinous contacts from Stat Control, Ford, and Hughes, Thornton began assembling a team of scientists and executives. As the new Litton’s formative years went by, quite a few smaller companies producing key technologies were acquired as well. Thornton’s initial focus for his new company was the production of cold war military hardware. Although they produced a wide variety of systems and hardware, the new Litton Industries soon became the leader in aircraft inertial guidance systems. As the years went by, however, Litton Industries began acquiring many different kinds of businesses. Thornton was consciously creating a new type of corporation. As time went on, Litton became known as a ‘conglomerate.’ Other conglomerates of the time included International Telephone and Telegraph (which conducted lots of business with Nazi Germany), Textron, and Ling-Temco-Vought. Textron and Ling-Temco-Vought have extensive ties to the New Manhattan Project.

Litton Industries was another big success and Litton has many connections to the New Manhattan Project. Litton has produced: over the horizon radar and remote sensing technologies, the aforementioned aircraft inertial guidance systems, many technologies for America’s space program, command and control system technologies, micro-electromechanical devices, as well as meteorological technologies and services. Litton produced these technologies for many organizations most probably responsible for the production and execution of today’s New Manhattan Project such as: the Air Force, the Navy, the National Atmospheric and Space Administration (NASA), the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), and the Atomic Energy Commission. For the relevance of all these things to today’s New Manhattan Project, please refer to the author’s book.

Being that the New Manhattan Project is mainly about weather control, of all the areas applicable to the New Manhattan Project in which Litton has been involved, the most salient are those involving meteorological technologies and services. For this reason, we will now look extensively at Litton’s involvement in the area of meteorology.

For America’s manned moon missions, Litton produced weather fax recorders, which received continuous weather data feeds from the United States Weather Bureau and the United States Air Force Weather Transmitting Network.

In 1996 Litton acquired a company called PRC Inc. This acquisition strengthened Litton’s Information Systems group which, among other things, provided weather information. Jeffrey Rodengen, author of the book The Legend of Litton Industries writes:

The National Weather Service adopted PRC’s interactive weather computer and communication system, called the Advanced Weather Interactive Processing System (AWIPS). This computer system essentially tied together the weather data from satellites and radar and analyzed it to produce a more accurate weather forecast. The accuracy was a result of a ‘much faster, more powerful computer system to analyze the data,’ explained PRC President Leonard Pomata.

By the end of 1999, Litton expected to install more than 150 of these systems in offices around the country. The system earned the 1997 Technology Program of the Year award from Popular Science magazine, as well as the Smithsonian Institution’s 1999 Laureate Award, which recognizes technology that improves social and community life.

In 1998 Litton acquired TASC, Inc. TASC, Inc. came complete with their Weather Services International unit. Rodengen informs us once again:

Weather Services International (WSI), a unit of TASC, supplied real-time weather data, imagery and forecast services to aviation, utilities, government and agricultural markets, as well as broadcast-ready weather programming and graphics systems to national media. From its own meteorological operations center, WSI provided weather information services to 50 percent of the country’s television stations, plus live, on-air reports to cable outlets such as Fox Cable News. Also, most major domestic airlines contracted with WSI for meteorological services.

Together, TASC and PRC put Litton among the leaders in the commercial and federal weather systems markets. By 1999, newscast agencies on the internet, television, radio and other media bought more than 90 percent of their weather information analysis and graphical representation from these two divisions.

Litton has produced micro-electromechanical devices (MEMs) that can sense atmospheric temperature and pressure. They have also produced klystron tubes for weather radars. But the most interesting evidence for our investigation appears in a 1969 book written by Beirne Lay, Jr. titled Someone Has to Make It Happen: The Inside Story of Tex Thornton, the Man Who Built Litton Industries. Lay writes:

Through the atmosphere window he [Thornton] mused over the possibilities of modifying or controlling the vagaries of the weather for the better distribution of rainfall, the prediction of tornadoes and hurricanes, the amelioration of hostile climatic conditions, and, as in space, the achievement of such accuracy in navigation that an airliner could fly from Los Angeles to Tokyo, automatically and without ground stations, without missing the airport by more than a mile. He mulled over the potentials of new devices such as lasers to relieve already crowded channels of communication through the atmosphere and to create better electronic systems of command and control for the military’s ever more sophisticated demands.

~ ~ ~

At his last board meeting, Tex Thornton requested that his son, Charles B. Thornton, Jr. be named to the board of directors. Tex Thornton died on November 24, 1981. In 2000 Litton Industries was acquired by Northrop Grumman.

References

The Rise and Fall of the Conglomerate Kings a book by Robert Sobel, published by Stein and Day, 1984

The Whiz Kids: Ten Founding Fathers of American Business – and the Legacy They Left Us a book by John A. Byrne, published by Doubleday, 1993

U.S. patent #5,003,186 “Stratospheric Welsbach Seeding for Reduction of Global Warming” by David B. Chang, 1991

The Legend of Litton Industries a book by Jeffrey L. Rodengen, published by Write Stuff Enterprises, 2000

Someone Has to Make It Happen: The Inside Story of Tex Thornton, the Man Who Built Litton Industries a book by Beirne Lay, Jr., published by Prentice Hall, 1969

Wall Street and the Rise of Hitler a book by Antony Sutton, published by Buccaneer Books, 1976

“Northrup to Buy Litton in a $3.8-Billion Deal” an article by Peter Pae, published in The Los Angeles Times, Dec. 22, 2000

Links

PeterAKirby.com

My Minds page

My Steemit page

My GoodReads page

My YouTube channel

My BitChute channel

Websites

ClimateViewer.com

StopSprayingCalifornia.com

ChemSky.org

NuclearPlanet.com

GlobalSkyWatch.com

ChemtrailsProject.com

ChemtrailsProjectUK.com

ChemtrailSafety.com

GeoengineeringWatch.org

Peter A. Kirby is a San Rafael, CA researcher, author, and activist. Please buy the greatly revised and expanded second edition of his book Chemtrails Exposed: A New Manhattan Project available now exclusively at Amazon. Also please join his email list at his website PeterAKirby.com.

Subscribe to Activist Post for truth, peace, and freedom news. Send resources to the front lines of peace and freedom HERE! Follow us on SoMee, HIVE, Parler, Flote, Minds, and Twitter.

Provide, Protect and Profit from what’s coming! Get a free issue of Counter Markets today.

Be the first to comment on "Tex Thornton and the New Manhattan Project"