By B.N. Frank

By B.N. Frank

If/when an entity ever convinces your municipality or county to burn trash in an effort to reduce greenhouse gasses and create energy, this could lead to devastating consequences.

From the Minneapolis Post:

Twin Cities residents push for environmental justice; combatting the effects of environmental racism

There’s an urgency in affected communities to get polluting facilities out of their neighborhoods.

“It reeks of environmental racism…It reeks of classism…It reeks of the smell of death.”

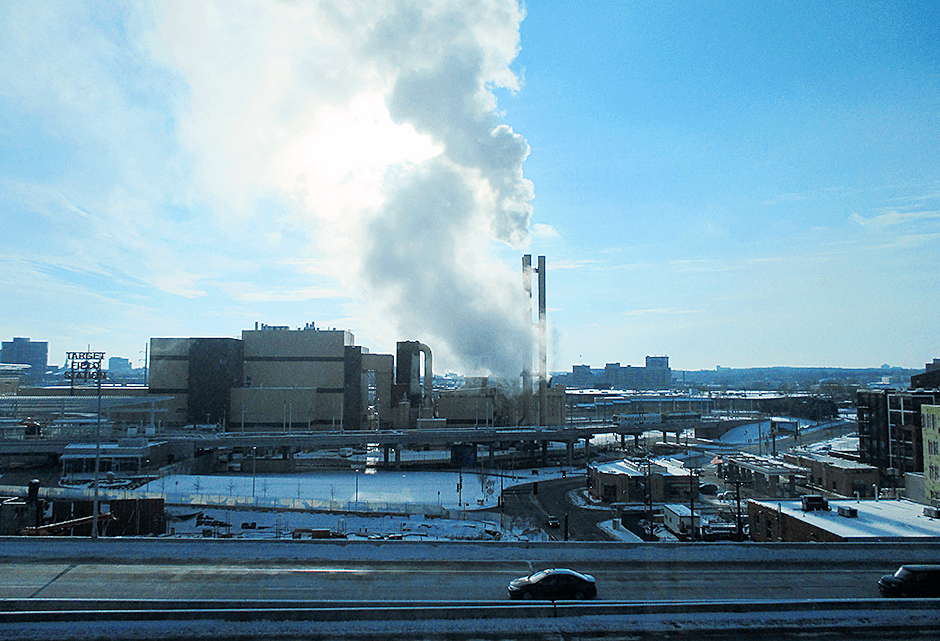

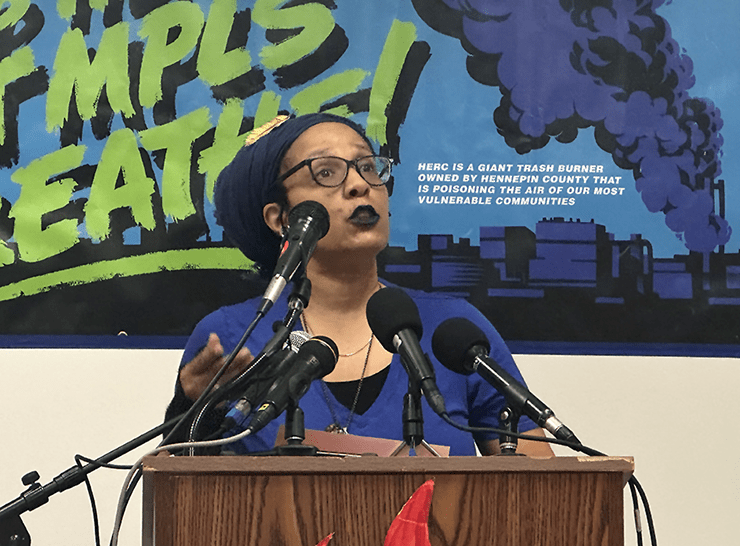

Those were some of the words Stephani Maari Booker used to condemn the effects of pollution from the Hennepin Energy Recovery Center (HERC), a trash incinerator and energy converted in north Minneapolis.

Booker, a Minneapolis writer and community volunteer for the Minnesota Environmental Justice Table, was one of a few speakers at a press conference on Feb. 7 that introduced the People’s HERC Transition Plan. This plan, created by Zero Waste USA under contract with Minnesota Environmental Justice Table – one of the members of the Zero Burn Coalition, which hosted the press conference – seeks to close the Hennepin Recovery Energy Center by the end of 2025. Painted signs at the press conference had a variety of messages printed on them, many of which referenced the incinerator’s negative impact on the health of surrounding communities.

Booker herself lives in the 55411 zip code, where asthma rates are nearly five times more than that of the state as a whole. Her zip code neighbors where the HERC is located. As she spoke at the press conference, Booker mentioned her previous involvement helping formulate the county’s 2020 Zero Waste Plan and her disappointment with the board of county commissioners’ recent decisions regarding HERC.

“Behind closed doors and out of public view, the board decided to extend the contract with the trash burner to 2033,” Booker said, adding that this had taken place the day before the Feb. 7 press conference without public comment.

“As a north Minneapolis resident, as someone whose input was solicited for the county’s zero waste plan, and as a human being with a mind, a heart and especially lungs, I feel betrayed by Hennepin County,” Booker said.

The HERC

The Hennepin Energy Recovery Center was built in 1989 and currently takes in trash from Minneapolis and outlying areas. According to the county, the HERC emits less greenhouse gasses than landfills and minimizes pollution. But according to members of the Zero Burn Coalition, this is a misrepresentation of the HERC’s pollution and waste.

“Even if you ship trash hundreds of miles to a landfill the landfill would still emit less greenhouse gas than burning the trash” said Nazir Khan, co-founder of Minnesota Environmental Justice Table, a part of the Zero Burn Coalition. Additionally, Khan said, after the trash is burned, the remaining ash still ends up in an ash landfill.

For Charles Frempong-Longdon Jr., the communications organizer at Minnesota Environmental Justice Table, conversations about the emissions and magnitude of pollution from the HERC can distract from discussion of its real impacts on human health.

“We’re pushed into making these hypothetical comparisons between landfills and trash incinerators when there’s an actual garbage burner in downtown Minneapolis that’s harming people’s health,” Frempong-Longdon said. “People are experts in their own health and have been really sounding the alarm for this since it was built. … If you’re acknowledging that it’s harming people, why are we taking it to a different place instead of focusing on that?”

According to research conducted by PSE Healthy Energy, the HERC’s pollution has led to $16 million in health damages, making it the “most impactful facility in Hennepin County.”

A Hennepin County representative, when contacted, sent along a statement saying that air emissions from HERC have always been lower than permitted and have a negligible impact on health. According to the representative, closing the HERC “prematurely” would also not address the “main drivers of health problems” such as access to insurance, health care, housing and employment.

Beyond the HERC: Environmental racism in the Twin Cities

The impacts of the HERC are not the only marks of what is being termed environmental racism in the Twin Cities. In a 2020 article for the Vanderbilt Law Review, civil rights lawyer Deborah Archer, president of the American Civil Liberties Union, examined how the construction of federal highways displaced Black communities across the United States. According to Archer, the construction of Interstate 94 through Minnesota displaced one-seventh of St. Paul’s Black residents and destroyed the Black community of Rondo. Seven hundred homes and 300 businesses, according to the Reconnect Rondo project, were shut down or demolished in Rondo to construct the I-94.

The effects of this displacement and construction of the highway have led to long-term health concerns for residents in the area. Those living around the section of the I-94 between Minneapolis and St. Paul have a rate of asthma hospitalization that is nearly three times that of the state as a whole.

One of these affected communities is East Phillips in south Minneapolis. From 1938 to 1963, the CMC Heartland Partners Lite Yard site – a site for the production and storage of arsenic by US Borax – was located in East Phillips. Later in 1994, when Hiawatha Avenue was being reconstructed, high levels of arsenic were found in the soil and groundwater of the site. More recently, the Smith Foundry, a factory producing iron castings, was notified in 2023 that the Environmental Protection Agency had found potential violations of the Clean Air Act during inspection. While the agency’s federal investigation is ongoing, it is worth noting that the 55404 and 55407 zip codes, which make up parts of East Phillips, both have higher rates of asthma hospitalizations than Minnesota as a whole.

A representative of the Smith Foundry, when contacted, referenced a BusinessWire release stating that the Environmental Protection Agency and the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency had found the Foundry’s air emissions in compliance.

Bad air, unheard voices

Last year, Booker, who lives in Near North, went out to her garden before getting a phone call from her mother urging her to go back inside. Due to wildfires in Canada, there was a statewide air quality emergency, which made the air in Minnesota dangerous to breathe.

Outside in her garden, Booker hadn’t even noticed the air was that bad.

“I often smell smoke, all the time. I often smell just generally bad smells here all the time. I couldn’t tell the difference between how it is normally around here and an air quality emergency,” said Booker.

Near North resident and author Stephani Maari Booker spoke at the Zero Burn Coalition’s press conference introducing the People’s HERC Transition Plan. Credit: MinnPost photo by Deanna Pistono

B. Rosas, policy manager at Climate Generation, grew up near the East Phillips neighborhood in south Minneapolis. Though they only realized the magnitude of the pollution when they were older, growing up around pollution affected their family and friends.

“I had a lot of family who (would) carry children and they would lose it,” Rosas said. “As I grew older, I found out that’s a really big response to a lot of the pollution that’s happening … sometimes, in the summer, we would be told to close the window because the air was smoky outside.”

There’s an urgency in affected communities, Rosas said, to get polluting facilities out of their neighborhoods. Smith Foundry, they said, “is right across the street from a daycare center.” But community urgency has not led to enough action by local governments complained Rosas.

“When it comes down to environmental racism in the state of Minnesota, it’s not only these big industries who are coming and polluting,” Rosas said. “It’s the state agencies that are also not listening to residents when they mention that these facilities are harmful.”

While the county has attempted to reach out to community members about environmental justice, community organizers and volunteers have different criticisms about the outreach that has taken place.

Booker was one of the community members who participated in Hennepin County’s Zero Waste Plan Community Group and was placed with the Equity and Access Action Group. Though she was initially happy to be part of this group in order to create a plan, Booker wrote in an unpublished op-ed, she found the process of submitting feedback to be inaccessible and difficult, which she wrote was ironic, given that she was part of a group focused on accessibility.

For Rosas, a major issue is which voices are being prioritized by decision makers.

“A large part of the environmental justice fight is prioritizing people over profits,” Rosas said. “It’s more than just a saying, it’s a practice. And it’s a practice that we’re really needing our state agencies to take a little bit more seriously.”

“Fundamentally, I think certain communities are designated as sacrifice communities, and where they live as sacrifice zones. You can put all the crap in where they live, and that’s just (the) cost of doing business, basically. Some people die, some people get sick,” Khan said, calling this attitude a deep moral problem that this society doesn’t really reckon with. “At what cost is profit and greed? Is there anything that isn’t worth that sacrifice? Human life, for example?”

Deanna Pistono is MinnPost’s Race & Health Equity fellow. Follow her on Twitter @deannapistono or email her at dpistono@minnpost.com.

Activist Post reports regularly about environmental toxins. For more information, visit our archives.

Top image: Pixabay

Become a Patron!

Or support us at SubscribeStar

Donate cryptocurrency HERE

Subscribe to Activist Post for truth, peace, and freedom news. Follow us on SoMee, Telegram, HIVE, Minds, MeWe, Twitter – X, Gab, and What Really Happened.

Provide, Protect and Profit from what’s coming! Get a free issue of Counter Markets today.