By Neenah Payne

By Neenah Payne

How would you use Roman numerals to add or subtract – much less multiply or divide?! Today, we take the Arabic numbering system with the concept of zero for granted. However, “the something that is nothing” was a very radical idea when it was introduced to Europe in the ninth century and the Catholic Church rejected it as “Saracen magic” for centuries. Europe knew that India used the zero, but it rejected the concept until the Muslims adopted it and explained it.

Persian mathematician, Mohammed ibn-Musa al-Khowarizmi (c.778 – c.850) introduced the Hindu-Arabic numbers to Europe when he worked in The House of Wisdom in Baghdad. Al-Khwarizmi referred to zero as ‘sifr,’ from which we get our word “cipher”. He published his renowned book, Al-Kitāb al-mukhtaṣar fī ḥisāb al-jabrwal-muqābala, from which the term ‘algebra’ was derived (al-jabr). He also created quick methods for multiplying and dividing numbers known as algorithms. See The Father of Algebra: Al-Khwarizmi.

By 879, the dot had become an oval shape that closely resembled the modern zero. In the middle of the 12th century, Al- Khwarizmi’s work had made its way to England. Italian mathematician Fibonacci (1170-1250), who had been educated by Arabs, developed the number further by using it to do equations without an abacus. By the 1600s, the zero had spread widely throughout Europe.

The zero was fundamental in the Cartesian coordinate system of Rene Descartes (1596-1650) and in calculus created by Sir Isaac Newton (1643-1727) and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646-1716). Later, calculus paved the way for physics, engineering, computers, and most modern financial and economic theories. The zero makes it much easier to conceptualize trade and business. Computers and all technologies connected with them rely on the use of 1s and 0s.

The Nothing That Is

Melvyn Bragg and guests discuss the history of the number between 1 and -1, which has strange and uniquely beguiling qualities. Shakespeare’s King Lear warned, “Nothing will come of nothing”. The poet and priest John Donne said from the pulpit, “The less anything is, the less we know it: how invisible, unintelligible a thing is nothing”, and the English monk and historian William of Malmesbury called them “dangerous Saracen magic”.

They were all talking about zero, the number or symbol that had been part of the mathematics in the East for centuries, but was finally taking hold in Europe. What was it about zero that so repulsed their intellects? How was zero invented? And what role does zero play in mathematics today?

With Robert Kaplan, co-founder of the Maths Circle at Harvard University and author of The Nothing That Is: A Natural History of Zero; Ian Stewart, Professor of Mathematics at the University of Warwick; Lisa Jardine, Professor of Renaissance Studies at Queen Mary, University of London.

The Nothing That Is: A Natural History of Zero

Amazon Description

A symbol for what is not there, an emptiness that increases any number it’s added to, an inexhaustible and indispensable paradox. As we enter the year 2000, zero is once again making its presence felt. Nothing itself, it makes possible a myriad of calculations. Indeed, without zero, mathematics as we know it would not exist. And without mathematics, our understanding of the universe would be vastly impoverished. But where did this nothing, this hollow circle, come from? Who created it? And what, exactly, does it mean?

Robert Kaplan’s The Nothing That Is: A Natural History of Zero begins as a mystery story, taking us back to Sumerian times, and then to Greece and India, piecing together the way the idea of a symbol for nothing evolved. Kaplan shows us just how handicapped our ancestors were in trying to figure large sums without the aid of the zero. (Try multiplying CLXIV by XXIV).

Remarkably, even the Greeks, mathematically brilliant as they were, didn’t have a zero–or did they? We follow the trail to the East where, a millennium or two ago, Indian mathematicians took another crucial step. By treating zero for the first time like any other number, instead of a unique symbol, they allowed huge new leaps forward in computation, and also in our understanding of how mathematics itself works.

In the Middle Ages, this mathematical knowledge swept across western Europe via Arab traders. At first it was called “dangerous Saracen magic” and considered the Devil’s work, but it wasn’t long before merchants and bankers saw how handy this magic was, and used it to develop tools like double-entry bookkeeping. Zero quickly became an essential part of increasingly sophisticated equations, and with the invention of calculus, one could say it was a linchpin of the scientific revolution. And now even deeper layers of this thing that is nothing are coming to light: our computers speak only in zeros and ones, and modern mathematics shows that zero alone can be made to generate everything.

Robert Kaplan serves up all this history with immense zest and humor; his writing is full of anecdotes and asides, and quotations from Shakespeare to Wallace Stevens extend the book’s context far beyond the scope of scientific specialists. For Kaplan, the history of zero is a lens for looking not only into the evolution of mathematics but into very nature of human thought. He points out how the history of mathematics is a process of recursive abstraction: how once a symbol is created to represent an idea, that symbol itself gives rise to new operations that in turn lead to new ideas. The beauty of mathematics is that even though we invent it, we seem to be discovering something that already exists.

The joy of that discovery shines from Kaplan’s pages, as he ranges from Archimedes to Einstein, making fascinating connections between mathematical insights from every age and culture. A tour de force of science history, The Nothing That Is takes us through the hollow circle that leads to infinity.

Zero: The Biography of a Dangerous Idea

Amazon Description

Popular math at its most entertaining and enlightening. “Zero is really something”-Washington Post

A New York Times Notable Book.

“The Babylonians invented it, the Greeks banned it, the Hindus worshiped it, and the Church used it to fend off heretics. Now, it threatens the foundations of modern physics. For centuries the power of zero savored of the demonic; once harnessed, it became the most important tool in mathematics. For zero, infinity’s twin, is not like other numbers. It is both nothing and everything.

In Zero, Science Journalist Charles Seife follows this innocent-looking number from its birth as an Eastern philosophical concept to its struggle for acceptance in Europe, its rise and transcendence in the West, and its ever-present threat to modern physics.

Here are the legendary thinkers—from Pythagoras to Newton to Heisenberg, from the Kabalists to today’s astrophysicists—who have tried to understand it and whose clashes shook the foundations of philosophy, science, mathematics, and religion. Zero has pitted East against West and faith against reason, and its intransigence persists in the dark core of a black hole and the brilliant flash of the Big Bang. Today, zero lies at the heart of one of the biggest scientific controversies of all time: the quest for a theory of everything.

The Origin of Zero

The story of zero: How ‘nothing’ changed the world (audio)

‘We often take it for granted. But it’s one of the greatest inventions of all time,’ says mathematician Charles Seife.

Modern life would not be possible without zero and the concept of nothing. Thanks to mathematicians embracing the confounding paradoxes of zero to harness its power, remarkable technologies have been created, from satellites to space travel.

*This is the first episode in our series, The Greatest Numbers of All Time.

Mathematician Charles Seife is interviewed in the podcast above. He is a professor of journalism, director of NYU’s Arthur L. Carter Journalism Institute, and the author of Zero: The Biography of a Dangerous Idea. He says:

For early Christians, the very existence of God relied necessarily on a refutation of any absolute void – and zero had no place in the church’s cosmology. Greek philosophy, and by extension early Christian philosophy, more or less rejected the idea of nothing. It was dismissed. We often take it for granted. But it’s one of the greatest inventions of all time.

The article says: “Ian Stewart points to zero, to mathematics, and to physics ‘and everything that goes with it’ as the hero for propelling us out of the Middle Ages into the modern world.”

Why The Catholic Church Condemned The Zero

By 1200, European bankers were adopting Arabic numbers. However, Seife says that in 1299, the Catholic Church banned the use of Arabic numerals, saying they represented Satan! However, in the Renaissance, Christian scientists realized they weren’t going to make progress without switching to Arabic numbers. By the 14th century, the zero was finally adopted by all of Europe. Selfie said that if the Arabic numbers had not been adopted then, the Renaissance would have been delayed.

Zero & Christianity points out:

The Church’s Fear of Math

The study of mathematics posed a serious threat to early Christians. To them it was tantamount to inquiring into God’s mind and as such it was considered heretical. According to Christians there was no way that a mathematician could be a Christian. The two were mutually exclusive. This was as a result of the Church’s total acceptance of the Aristotelian cosmological view.

The fact is that Christians were opposed to mathematics because of two important mathematical concepts, zero and infinity…. While Christianity avoided the concept and symbol of zero (it was a symbol of the devil!!!) both Hinduism and Buddhism embraced it with open arms. Early Christian philosophy could not accept the void or nothingness, but the void, however, was fundamental to other ancient eastern religions.

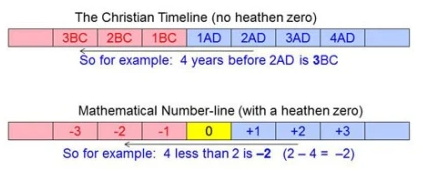

So afraid of zero were the early Christians that the Venerable Bede, a monk preparing the Christian calendar, around the year 731, left out the year zero. The Christian Timeline is shown below where, as can be seen, the year zero is left out. This is quite different from our present-day mathematical number line. Every school child nowadays is familiar with the number line with zero separating the positive integers from the negative integers.

The outlook of Christians was fundamentally different from that of the ancient Greeks, who were extremely interested in mathematics and science. According to Christians God revealed himself through the Bible and the Church.

As Tertullian (third century Church author) explained, scientific research became superfluous once the gospel of Jesus Christ was available:

We have no need of curiosity after Jesus Christ, nor of research after the gospel. When we believe, we desire to believe nothing more. For we believe that there is nothing else that we need to believe. (http://www.badnewsaboutchristianity.com/ea0_trad.htm)

While Christianity avoided it, (like the plague) Islam readily accepted the concept of the void. It migrated from India around the 8th century and found a ready home in Islam. according to Dirk J Struik, “Islamic activities in the exact sciences, which began with Al-Fazari’s translation of the ‘Siddhantas’ reached its first height with a native from Khiva, Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarimi, who flourished about the year 825.” (Dirk A Struik, A concise history of mathematics.)

Fibonacci enlightens Europe.

In the year 1202, zero was carried to the West by an Italian mathematician, Leonardo de Pisa, (Fibonacci) who had become enthralled with the Hindu-Arabic numerals including zero. He was introduced to them by the Muslims while traveling in North Africa. He later took his new found knowledge back to Europe in his book Liber Abaci.

His book was looked upon with fascination in the West. Many merchants and traders found the Hindu-Arabic numerals easier to use than the old Roman numerals. Nevertheless, the Church refused to accept the “heathen symbol”, that accursed zero. It represented that which was an anathema to Church doctrine, the void. For according to Aristotle, there could be no void. (Physics, Book IV) The Aristotelian doctrine was the doctrine of the Church.

However, a new wind was blowing. In 1543 Nicholaus Copernicus, a Polish monk, published his great work contradicting the Aristotelian doctrine and thereby shaking the very foundations of the Church. The Church was extremely unhappy about this and while Copernicus was the instigator, Giordano Bruno paid the ultimate price. Copernicus was able to escape the wrath of the Church probably because he died soon after the publication of his work. Not so fortunate, however, was Giordano Bruno who was burnt at the stake and Galileo Galilei who was severely admonished and ordered by the Church to desist from any further publication.

Notwithstanding the anger of the Church over the apparent cracks in its doctrine, the opposition continued and more of the faithful began to accept the modern theories and abandon the Aristotelian doctrine of the Church. The fact is that there were many within the Christian community who were quite torn between the old doctrine and the new.

Enter Rene Descartes

More and more the Catholic Church started losing control of its flock. In the 16th and 17th centuries, philosophers and theologians were gradually accepting the new philosophies. One such person was the mathematician and philosopher, Rene Descartes. “Rene Descartes was trained as a Jesuit, and he too, was torn between the old and the new. He rejected the void but put it at the center of his world.” (Charles Seife, Zero, the Biography of a Dangerous Idea.)

Although he recognized the symbol zero and used it in what is now known as his Cartesian plane, as a devout Catholic, he found it difficult to admit the existence of the void. He was torn between two loyalties. His loyalty to his faith won.

It was inevitable that the new ideas would overtake the Church and force its hands, however grudgingly, to abandon Aristotle and accept the new philosophy. I used the term grudgingly because even in the 18th century, mathematicians were still being ridiculed by prominent churchmen. Isaac Newton was severely criticized by Bishop Berkeley who said that Newton’s theory of fluxions was incompatible with Christianity. Quite a few prominent Churchmen still felt that way up to that time.

The View Today

Today most of us think differently. Even the Church has changed its views. ”Scientific research must be encouraged and promoted, so long as it does not harm other human beings, whose dignity is inviolable from the very first stages of existence,” Pope Benedict XVI said in June 2007, the New York Times reported. (https://www.livescience.com/27790-catholic-church-and-science-history.html)

Slowly the Church has changed its views on mathematics and science. No longer are mathematicians and scientists considered sorcerers and purveyors of black magic. (I am sure both Giordano Bruno and Galileo would have preferred to live in these enlightened times.)

Note: MEDIEVAL EUROPE’S SATANIC CIPHERS: ON THE GENESIS OF A MODERN MYTH refutes the idea that the Catholic Church initially rejected Arabic numbers.

Why Zero Was Banned For 1,500 Years

The video below is a fascinating review of the history of zero. However, it does not mention that Al-Khwarizmi introduced the Arabic numbering system to Europe. It also doesn’t mention that Fibonacci learned Arabic numbers because his father had him study with Arabs.

This is an example of how Europeans are given credit for the massive contributions of Muslims during the 500 years of The Golden Age of Islam which were the foundation of the Renaissance but have been written out of European history. In this way, Europe is said to have magically gone from the centuries of Dark Ages after the fall of Rome in 496 AD to the Renaissance despite the fact that all Europeans except the clergy were illiterate.

Why the number 0 was banned for 1500 years

The Importance of Zero

Why Zero Is So Ridiculously Important

What is Zero? Getting Something from Nothing – with Hannah Fry 4/13/16

Is zero really a number? How did it come about? Hannah Fry tells the story of how zero went from nothing to something.

“Zero is a strange beast. It took until the 7th century for it to be explicitly recognized as a number in its own right, when the ancient Indians developed a numerical system that expressed zero with its own symbol. Since the development of this number system, which we still use today, zero has been instrumental in our exploration of mathematics.

The human use of numbers sprang from the practical need to count things, but at the time zero was only used to denote an absence of value. In this light, could it even be considered a number? As human thought progressed, however, and mathematics became more of an abstract process to unravel reality, zero started to prove itself as a very useful tool. This animated video from The Royal Institution, narrated by mathematician Hannah Fry, tells the story of this winding history, from its role in ancient civilizations to our current world of computer technology, and explains how zero became a mathematical hero.”

The mind-bendy weirdness of the number zero, explained

We explain nothing.

The computer you’re reading this article on right now runs on a binary — strings of zeros and ones. Without zero, modern electronics wouldn’t exist. Without zero, there’s no calculus, which means no modern engineering or automation. Without zero, much of our modern world literally falls apart.

Humanity’s discovery of zero was “a total game changer … equivalent to us learning language,” says Andreas Nieder, a cognitive scientist at the University of Tübingen in Germany.

But for the vast majority of our history, humans didn’t understand the number zero. It’s not innate in us. We had to invent it. And we have to keep teaching it to the next generation.

Other animals, like monkeys, have evolved to understand the rudimentary concept of nothing. And scientists just reported that even tiny bee brains can compute zero. But it’s only humans that have seized zero and forged it into a tool.

So let’s not take zero for granted. Nothing is fascinating. Here’s why.

What is zero, anyway?

Our understanding of zero is profound when you consider this fact: We don’t often, or perhaps ever, encounter zero in nature. Numbers like one, two, and three have a counterpart. We can see one light flash on. We can hear two beeps from a car horn. But zero? It requires us to recognize that the absence of something is a thing in and of itself.

“Zero is in the mind, but not in the sensory world,” Robert Kaplan, a Harvard math professor and an author of a book on zero, says. Even in the empty reaches of space, if you can see stars, it means you’re being bathed in their electromagnetic radiation. In the darkest emptiness, there’s always something. Perhaps a true zero — meaning absolute nothingness — may have existed in the time before the Big Bang. But we can never know.

Nevertheless, zero doesn’t have to exist to be useful. In fact, we can use the concept of zero to derive all the other numbers in the universe. Kaplan walked me through a thought exercise first described by the mathematician John von Neumann. It’s deceptively simple….

What else can understand nothing?

We may not be born with the ability to understand zero. But our capacity to learn it may have deep evolutionary roots, as some new science shows us. The fourth step in thinking of zero — that is thinking of zero as a symbol — may be unique to humans. But a surprising number of animals can get to step three: recognizing that zero is less than one. Even bees can do it.

Scarlett Howard, a PhD student at Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology, recently published an experiment in Science that’s almost identical to the one Brannon did with kids. The bees chose the blank page 60 to 70 percent of the time. And they were significantly better at discriminating a large number, like six, from zero, than they were in discriminating one from zero. Just like the kids.

This is impressive, considering that “we’ve got this big mammalian brain but bees have a brain that’s so small weighs less than a milligram,” Howard says. Her research group is hoping to understand how bees do these calculations in their minds, with the goal of one day using those insights to build more efficient computers.

In similar experiments, researchers have shown that monkeys can recognize the empty set (and are often better at it than 4-year-old humans). But the fact that bees can do it is kind of amazing, considering how far they are away from us on the evolutionary trees of life. “The last common ancestor between us and the bees lived about 600 million years ago, which is an eternity in evolutionary times,” Nieder says.

We humans might have only come to understand zero as a number 1,500 years ago. What the experiments on bees and monkeys show us is that it’s not just the work of our ingenuity. It’s also, perhaps, the culminating work of evolution. There are still great mysteries about zero. For one, Nieder says “we hardly know anything” about how the brain physically processes it. And we don’t know how many animals can grasp the idea of nothing as a quantity. But what mathematics has clearly shown us is that when we investigate nothing, we’re bound to find something.

How Islamic Science Fueled The European Renaissance

Islamic Science and the Making of the European Renaissance

Amazon Description

The rise and fall of the Islamic scientific tradition, and the relationship of Islamic science to European science during the Renaissance. The Islamic scientific tradition has been described many times in accounts of Islamic civilization and general histories of science, with most authors tracing its beginnings to the appropriation of ideas from other ancient civilizations—the Greeks in particular.

In this thought-provoking and original book, George Saliba argues that, contrary to the generally accepted view, the foundations of Islamic scientific thought were laid well before Greek sources were formally translated into Arabic in the ninth century. Drawing on an account by the tenth-century intellectual historian Ibn al-Naidm that is ignored by most modern scholars, Saliba suggests that early translations from mainly Persian and Greek sources outlining elementary scientific ideas for the use of government departments were the impetus for the development of the Islamic scientific tradition.

He argues further that there was an organic relationship between the Islamic scientific thought that developed in the later centuries and the science that came into being in Europe during the Renaissance.

Saliba outlines the conventional accounts of Islamic science, then discusses their shortcomings and proposes an alternate narrative. Using astronomy as a template for tracing the progress of science in Islamic civilization, Saliba demonstrates the originality of Islamic scientific thought.

He details the innovations (including new mathematical tools) made by the Islamic astronomers from the thirteenth to sixteenth centuries, and offers evidence that Copernicus could have known of and drawn on their work. Rather than viewing the rise and fall of Islamic science from the often-narrated perspectives of politics and religion, Saliba focuses on the scientific production itself and the complex social, economic, and intellectual conditions that made it possible.

For More Information

Al-Razi: A Father of Western Medicine

How Coffee Created The Modern World

How Arabs Revolutionized Western Culture

How Islamic Architecture Transformed Europe

Europe’s Dark Ages Were Islam’s Golden Ages!

How Muslims Transformed Western Civilization

Ibn Sina/Avicenna: Founder of Western Medicine

How Muslims Inspired The European Renaissance

When Moors Rescued Europe From The Dark Ages

How The Islamic Golden Age Revolutionized The West

Ibn Rushd/Averroes: Grandfather of European Enlightenment

Neenah Payne writes for Activist Post

Become a Patron!

Or support us at SubscribeStar

Donate cryptocurrency HERE

Subscribe to Activist Post for truth, peace, and freedom news. Follow us on SoMee, Telegram, HIVE, Flote, Minds, MeWe, Twitter, Gab, and What Really Happened.

Provide, Protect and Profit from what’s coming! Get a free issue of Counter Markets today.

Be the first to comment on "How The Concept of Zero Changed The World!"