Rady Ananda

Rady Ananda

Activist Post

At the Justice Begins with Seeds biosafety conference held in Seattle August 2-3, it was announced that a recent court decision prevented Monsanto from suing farmers for patent infringement when their crops become genetically contaminated with lab-engineered patented seeds. But the ruling is insufficient to protect farmers in the real world, where contamination events are often much higher than only one percent of a field, as specifically prescribed in the ruling.

The June 2013 decision dismissing OSGATA v. Monsanto discussed in the letter by Jim Gerritsen, president of the Organic Seed Growers and Trade Association, protects farmers from being sued for “inadvertent contamination” of “approximately one percent” of their crops. Gerritsen sent the letter in lieu of his appearance.

That letter, reproduced at Good Food Web, has now gone viral, leading to some misunderstanding about the significance of the court’s decision and the protections afforded US farmers.

The court did bind Monsanto to a statement made on its website that it would not sue growers, seed sellers or organizations for inadvertently using or selling trace amounts of genetically modified seeds. The court defined “trace” this way:

While the USDA has not established an upper limit on the amount of trace contamination that is permissible, the appellants argue, and Monsanto does not contest, that ‘trace amounts’ must mean approximately one percent (the level permitted under various seed and product certification standards). We conclude that Monsanto has disclaimed any intent to sue inadvertent users or sellers of seeds that are inadvertently contaminated with up to one percent of seeds carrying Monsanto’s patented traits.

The court added, however, that anyone who replants or sells “even very small quantities of patented transgenic seeds without authorization may infringe any patents covering those seeds.” [emphasis added]

The court specifically stated:

For purposes of this appeal, we will assume (without deciding) that using or selling windblown seeds would infringe any patents covering those seeds, regardless of whether the alleged infringer intended to benefit from the patented technologies. [emphasis added]

On the farmers’ side, the court did not firmly decide the issue of inadvertent contamination, leaving its assumption ripe for further litigation.

On the farmers’ side, the court did not firmly decide the issue of inadvertent contamination, leaving its assumption ripe for further litigation.

Also on the farmers’ side, the June ruling clarified that a prior Supreme Court decision [Bowman v. Monsanto, 133 S.Ct. 1761 (2013)] “leaves open the possibility that merely permitting transgenic seeds inadvertently introduced into one’s land to grow would not be an infringing use.”

However, the bulk of the decision was a win for Monsanto, which admitted to suing or threatening suit against nearly 850 farmers between 1997 and 2010 for patent infringement, settling 700 of those cases before they reached trial.

Gerritsen understood and emphasized in his letter the key component of the ruling preventing Monsanto from suing farmers for trace contamination events when he asserted:

The estoppel protects EVERY farmer in the United States – not just those in our Plaintiff group.

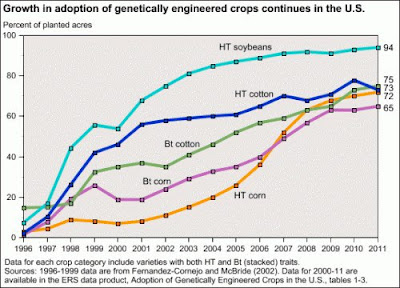

So the ruling has national impact, and that’s important. But having only one percent of your crops genetically contaminated is rare, especially for small farms, or those surrounded by GM fields. Already, over 90% of all soy and sugarbeets grown in the US are genetically modified, and about 66% of corn.

A case in point: By 2009, nearly a third of natural rice crops in the US had become genetically contaminated, as reported in a significant trial against biotech firm, Bayer AG. That lawsuit resulted in a $137 million award to Riceland Foods, a farmers cooperative spanning five states.

Though federal authorities today insist that there is no commercial GM rice growing in the US, in April, Turkish authorities arrested several people from companies that imported or distributed US rice which had tested positive for GM contamination. If not from commercial fields, then that contamination comes from ongoing trials or the 2006 contamination event which has not “been effectively eliminated,” as asserted by the US Embassy.

Can you imagine Monsanto executives being arrested for contaminating natural crops in the US? That would be a real victory for farmers and consumers. If corporations were held accountable for dangerous products that destroy the livelihood of others (given the collapse of export markets), the entire biotech industry would take a much more precautionary approach to GM deployment. Such is not the legal lay of the land, however.

|

| Alfalfa seeds are 2mm in size. Compare to field corn which is 13mm. |

When the US Supreme Court deregulated genetically engineered alfalfa in 2009, with its tiny seeds that can be windblown for miles, the organic beef and dairy industry took a hit because alfalfa is one of four staple crops used for free-range cattle. That was the first GMO case heard by the land’s highest court, and the victory went to biotech, thanks to former Monsanto attorney, Justice Clarence Thomas, who refused to recuse himself from the case.

By 2010, reports litigant Geertson Seed, US alfalfa had already been contaminated since GE alfalfa’s introduction in 2005. In 2011, the USDA approved widespread planting of the ubiquitous seed.

A mere one-percent contamination event would be rare, with much higher contamination penetration the most likely scenario. But, yes, it is good that all growers and distributors are now protected from suit by Monsanto when only 1% of their farmland or seed supply is genetically contaminated. That’s 1% better than nothing.

We need to remember that since the commercial deployment of GE crops in 1996, the federal government has consistently made it policy to promote the growth and spread of genetically engineered crops, here and abroad, as revealed in the diplomatic cables released by WikiLeaks.

In Section 733 of the 2013 Farm Bill, Congress stripped federal courts of the right to stop the sale and planting of genetically engineered crops during any legal appeals process. The Orwellian name, “Farmer Assurance Provision” has become widely known as the Monsanto Protection Act, though it applies to all biotech crops no matter who engineered them. That provision is set to expire next month, unless Congress approves its extension.

Though 95% of the US wants GMO foods labeled, California’s reported election results claimed that less than half voted for Proposition 37. We can thank electronic vote counting systems for that, given that those machines can be hacked without detection. Those vote results are unambiguously fraudulent. (Hand counted paper ballots, in full view of voters, would completely resolve the issue.)

Biotech companies, and their deadly products, are clearly at an advantage in the US.

OSGATA’s president, Jim Gerritsen, made it clear that the victory was in the ruling applying that 1% inadvertent contamination to all farmers, and not just the plaintiffs in that case. We have much more work to do to protect our farmers from Monsanto’s aggression against genetic contamination that Monsanto caused, and much more work to protect all of us from lab-created foods.

Rady Ananda is a researcher, writer, editor. Find more info at abact.wordpress.com/about/ Check out my blogs: COTO Report, coto2.wordpress.com and Food Freedom News, foodfreedomgroup.com. Or see my LinkedIn page: http://www.linkedin.com/pub/rady-ananda/44/719/a66

var linkwithin_site_id = 557381;

linkwithin_text=’Related Articles:’

Be the first to comment on "Monsanto can sue farmers when GMO contamination goes over one percent of their crop"