Story at-a-glance

- A preliminary American Heart Association (AHA) study linked long-term melatonin use to increased heart failure risk, but a closer analysis shows serious flaws, including lack of peer review and failure to account for confounding variables

- The study found melatonin users had 90% higher heart failure rates, but data mixed together prescription-only countries with over-the-counter markets, misclassifying many actual users as non-users

- Moreover, the study failed to account for insomnia severity, psychiatric conditions, other medications, and dosing details, making it impossible to determine if melatonin caused the observed outcomes

- Decades of peer-reviewed research demonstrates melatonin’s cardioprotective effects, including reducing blood pressure, protecting heart tissue, and mitigating oxidative damage, contradicting the study’s alarming headlines

- While supplementation is unlikely to pose serious risks, there are natural ways to optimize your melatonin production, such as getting morning sunlight exposure, keeping a consistent sleep schedule, limiting evening blue light, eating earlier, and practicing stress-reduction techniques

Sleep deprivation among Americans is growing at a concerning rate. According to the latest data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 39% of adults aren’t getting enough sleep (around seven hours each day).1 Proper high-quality sleep is important because it allows your body to rest and repair, and having irregular sleep patterns increases your risk of a whopping 172 diseases.

In an effort to curb sleep deprivation, experts started recommending the public to take melatonin supplements. In fact, consumers have become so reliant on them that the industry for melatonin supplements was valued at $2.84 billion in 2024.2

Now, a preliminary study throws a wrench at the longstanding belief that taking melatonin supplements helps improve sleep quality. According to the findings, which were presented at the American Heart Association’s (AHA) Scientific Sessions 2025, long-term use of melatonin supplements was linked to an increased risk in heart failure.3 But is there any truth to this?

Does Melatonin Truly Increase Heart Risk?

According to these preliminary findings, adults with chronic insomnia who used melatonin for at least a year had worse long-term heart outcomes than those who never had melatonin listed anywhere in their medical records. However, there are problems with this research that need to be taken into account.

•How the researchers defined melatonin users vs. nonusers — The research team pulled five years of electronic health records from the TriNetX Global Research Network, covering 130,828 adults.4 The melatonin group included people whose medical charts documented at least 12 consecutive months of melatonin use. The control group had insomnia but no record of melatonin in their files. Patients with a history of heart failure or any recorded prescription for other sleep drugs were excluded.

•Why the initial results raised concern about heart failure risk — Adults with chronic insomnia who had documented long-term melatonin use showed about a 90% higher rate of new heart failure diagnoses over five years compared to nonusers (4.6% versus 2.7%).

A secondary analysis also suggested that long-term melatonin users were nearly 3.5 times more likely to be hospitalized for heart failure compared to insomnia patients who never had melatonin listed in their medical records (19.0% versus 6.6%). The study also noted an increased likelihood of death from any cause in the melatonin-recorded group compared with nonusers.

•What happened when the team used a stricter definition of long-term melatonin use — They also created a second definition of long-term use — people who had at least two melatonin prescriptions written 90 days apart. This detail matters because melatonin is only available by prescription in countries like the United Kingdom.

When the data was re-analyzed with this stricter definition, the increased risk persisted — this time with an 82% higher chance of developing heart failure over five years compared to the matched nonuser group.

•Why the dataset’s structure may have distorted the comparison — The dataset mixed countries where melatonin requires a prescription with countries, like the United States, where most people buy it over the counter (OTC). Because the research counted only people whose melatonin use appeared inside an electronic medical record, anyone using OTC melatonin in the U.S. automatically got classified as a nonuser.

If you think about it, the analysis creates a strange situation. Documented melatonin users in this dataset were officially sicker, more medicated, or more doctor-dependent than the average person who casually takes melatonin at home. This is where the cracks in the study begin to show.

•Key limitations that weaken confidence in the findings — They didn’t have access to insomnia severity, psychiatric conditions like depression or anxiety, alcohol intake, shift-work patterns, or use of other sleep-enhancing substances.

As lead author Dr. Ekenedilichukwu Nnadi explained, “Worse insomnia, depression/anxiety or the use of other sleep-enhancing medicines might be linked to both melatonin use and heart risk.”5 This means the melatonin users in the study may not have been harmed by melatonin at all — they may simply have been the sicker group at baseline.

•How hospital coding practices may have exaggerated heart failure numbers — The AHA press release noted that hospitalization codes often include a wide range of related heart-failure-like entries, which inflate hospitalization counts beyond true new heart failure episodes.

This means the 3.5-fold hospitalization increase mentioned earlier possibly reflects how hospitals enter codes, not how the heart responds to melatonin. When you’re trying to understand whether your supplement choices are safe, it’s important to dig deep into the data to discern the truth.

•What the study failed to report about melatonin dose and timing — Your melatonin experience depends heavily on dose and timing, but none of this was highlighted in the press release. A person taking 1 milligram (mg) occasionally at night is wildly different from someone taking 10 mg nightly for years, yet the database treated them as identical. This lack of detail leaves you without a clear picture of what level of use the associations reflect.

A Clearer Breakdown and Critique of the AHA Study

The press release by the AHA has grabbed the attention of many health advocates, most notably GreenMedInfo founder Sayer Ji. In a Substack post, Ji corrects the narrative created by media coverage of the AHA study.6

Ji investigates how headlines distorted the conference presentation and why this matters for consumers. Ultimately, he wants to highlight that the fear triggered by the AHA press release was the result of scientific misunderstanding — not evidence that melatonin damages the heart.

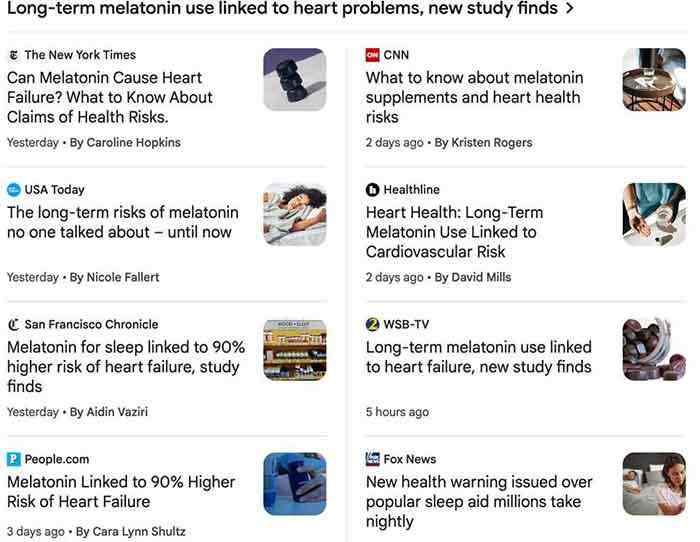

•Ji’s critique hinges on a single point — The AHA abstract was not a peer-reviewed study. He reiterates the AHA’s own words, saying “the findings are considered preliminary until published in a peer-reviewed journal.” However, mainstream media outlets treated the announcement as if it proved melatonin causes heart failure. Just look at the headlines he compiled in his Substack article:

This is an important distinction to make because preliminary abstracts are often incomplete, lack key variables, and serve as early scientific conversations, not final answers. Ji stresses that when journalists treat preliminary research as settled science, you are left with distorted health guidance.

•Mainstream media intentionally leaves out key details — Ji describes how numerous news platforms repeated the AHA’s claims verbatim, without any independent evaluation. He argues that this “media echo chamber” created widespread panic about a supplement with decades of research supporting its safety (shown later).

•Another key detail involves the way melatonin use was measured — Ji also pointed out how the AHA dataset only counted melatonin when it appeared as a prescription or documented medication in an electronic health record. It overlooks the fact that the majority of Americans buy melatonin over the counter, therefore making them invisible in the dataset.

This means the comparison between users and nonusers was fundamentally flawed — the so-called “nonuser” group almost certainly contained millions of real melatonin consumers whose use was unrecorded.

•Ji’s analysis also raises concerns about confounding variables — Specifically, he refers to factors that influence both insomnia and heart disease risk. He highlights that the AHA abstract excluded people taking benzodiazepines but did not adjust for other common sleep medications such as zolpidem (Ambien), eszopiclone (Lunesta), or trazodone. Ji notes that these drugs “carry well-documented cardiometabolic risks,” yet the abstract treated their use as irrelevant.

For anyone trying to understand whether melatonin itself is worrisome, this distinction matters. When a study fails to separate melatonin use from riskier sleep drugs, the results cannot tell you which factor caused the observed outcomes.

•Another overlooked layer involves other medications common in people with insomnia — Continuing the point above, Ji noted that the study did not account for the use of statins, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), or antihypertensives, even though all three drug classes influence cardiovascular pathology and sleep patterns.

This strengthens the argument that the data reflects the health status of medically complicated patients rather than the effects of melatonin. Once you realize this, the fearmongering generated by mainstream media makes far less sense.

•Ji brings evidence showing melatonin’s long-established cardioprotective effects — His article points to decades of peer-reviewed research demonstrating that melatonin provides three key benefits:

◦Reduces blood pressure and improves endothelial function

◦Protects mitochondria and heart tissue after ischemic injury

◦Mitigates oxidative damage and inflammation across numerous organs

These points are essential. If melatonin had a track record of harming the heart, it would show up consistently in the scientific literature. Instead, we see the opposite.

•The AHA needs to be held accountable — Ji closes his critique with an argument that if the AHA wants to repair its reputation, they need to stop pushing unreviewed findings into the public without context. He emphasizes:7

“If the AHA wishes to reclaim credibility, it should insist that findings of this magnitude be fully peer-reviewed, transparently replicated, and contextualized within the broader body of evidence — rather than rushed into public consciousness as a fear-inducing soundbite.”

How to Address Your Melatonin Production Naturally

Ji’s arguments are sound. The AHA study is only observational — based on a deeply flawed data set — and does not show causation. Moreover, there’s plenty of evidence supporting the cardioprotective benefits of melatonin. Having said that, supplemental melatonin isn’t the ideal solution for sleeplessness as it does not address the root of the problem, which is a disrupted circadian rhythm.

If you’re having trouble sleeping properly, getting sun exposure at the right time of the day is the best way to optimize melatonin production and restore your body clock. Here are helpful recommendations to get you started:

1.Sun exposure triggers your mitochondria to make melatonin — Most of the melatonin in your body forms inside your mitochondria as part of your built-in antioxidant system. Direct sunlight on your skin — especially the near-infrared wavelengths that pass through tissue — activates the signals your cells rely on to produce mitochondrial melatonin.

Window glass blocks key wavelengths and sunscreen blocks UV, so inadequate sun exposure leaves your mitochondria without the cue they need to maintain this protective melatonin supply.

2.Calibrate your internal clock — Your body depends on early daylight to recalibrate its internal clock every morning. Make it part of your routine to go outdoors shortly after you wake up, ideally within the first hour. Aim for 10 to 15 minutes of direct sunlight each morning (skip the sunglasses during this time).

3.Stick to a steady sleep-wake routine — Try settling into a consistent pattern by going to bed and waking up around the same time daily, weekends included. If shifting your schedule feels tough, move your bedtime earlier in slow increments — about 15 minutes every few days — until it aligns with your natural rhythm. To help improve your overall sleep quality, read “Top 33 Tips to Optimize Your Sleep Routine.”

4.Minimize exposure to artificial light two hours before bedtime — Bright indoor lighting, especially blue-light from screens and light-emitting diodes (LEDs), signals your brain that it’s still daytime, shutting down melatonin production.

To support your nightly wind-down routine, dim your lights after sunset and keep screen time to a minimum as bedtime approaches. If you need to use a device, switch on night mode or wear blue-blocking glasses.

5.Align your eating pattern with daylight — Your metabolism follows daily, consistent rhythms tied to daylight, and irregular eating habits can disrupt your body clock. Try to have your main meals earlier in the day and finish dinner at least three hours before going to sleep.

6.Incorporate mindfulness practices — Your circadian rhythm is tightly linked to how your body handles stress. Techniques such as meditation, yoga, breathwork, or other mindful practices help calm the stress-response system, making it easier for your internal clock to stay in sync.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) About the Connection Between Melatonin and Heart Failure

Q: Does long-term melatonin use actually increase the risk of heart failure?

A: In a preliminary study by the American Heart Association (AHA), researchers linked long-term melatonin use to a higher rate of heart failure diagnoses, hospitalizations, and all-cause mortality.

However, the data only tracked melatonin recorded in medical records. This means almost all over the counter melatonin users in the U.S. were labeled as “nonusers,” making the comparison deeply flawed. Researchers also lacked information about insomnia severity, psychiatric conditions, alcohol intake, other sleep drugs, or lifestyle factors — all of which directly influence heart risk.

Q: Why did the study show such alarming numbers if melatonin itself isn’t the problem?

A: The study’s “melatonin users” were not typical healthy supplement users. They were individuals whose melatonin use appeared in medical records, meaning they were sicker, more medicated, and more likely to be treated for complex conditions. This skewed the data, which reflected a high-risk population, not a harmful supplement.

Q: Did the mainstream media accurately report the AHA findings?

A: No. The press release clearly stated the data was “preliminary” and not peer-reviewed, but major news outlets reported it as definitive proof that melatonin causes heart failure. GreenMedInfo founder Sayer Ji highlighted that media outlets copied the AHA talking points without evaluating the study’s limitations. This created an echo chamber of fear-driven headlines despite the study’s weak design and major data gaps.

Q: What important details did the AHA study fail to include?

A: The dataset did not track melatonin dose or timing, so a person taking 1 mg occasionally was treated the same as someone taking 10 mg nightly for years. It also did not adjust for common sleep drugs (like Ambien, Lunesta, and trazodone), statins, SSRIs, or blood pressure medications — all of which influence heart function. Hospitalization counts were inflated due to broad diagnostic coding, further distorting results.

Q: Is melatonin actually harmful to the heart?

A: The broader scientific evidence does not support that conclusion. Decades of research show melatonin lowers blood pressure, protects mitochondria, reduces oxidative damage, improves endothelial function, and supports recovery after cardiac injury.