The doomsayers of the 1890s saw our cities drowning in horse poop. The doomsayers of the 1930s saw a final battle between freedom and fascism. The doomsayers of the 1950s and 60s saw the Cold War ending in nuclear apocalypse. The doomsayers of the 1980s saw the world about to boil with global warming. The doomsayers of 2001 saw a final reckoning between 1.5 billion Muslims and 2 billion Christians. The doomsayers of 2020 saw a rerun of the Black Death.

They were all wrong. Terrible wars and huge losses did occur, but in spite of them, human progress has been relentless. Every decade of the modern era has ended with more people living longer on this planet. Threats were real, but underneath it all we humans still kept making headway, improving life on average for the masses.

What was feared was averted, in short, by competition. Every region stupid enough to regress towards stagnancy or destruction was taken over by those who instead chose progress, helped by the technological advantages that came with that progress. The Austrian and Ottoman Empires thereby met their ends. Every ideology arrogant enough to challenge too many neighbours with too much hatred and oppression was eventually taken down a peg by those neighbours, as was seen with Nazi Germany or colonial-era France and England.

Today, those in power are once more on a destructive rampage in most countries of the world. We live in a time of neo-feudalism, with the powerful hanging on to their privileges and harvesting new ones by starting wars, announcing health crises, and surveilling the hell out of us. It would be easy to cry doom again and say times are terrible.

Yet even in the midst of horror, it is vital – if we wish to find the hope and courage to fight on – to stop and smell the roses. What good things are happening in the world, and what is still truly good about the West? Settle in for a joyful reckoning that we hope will put a smile on your face.

Five Positive Trends

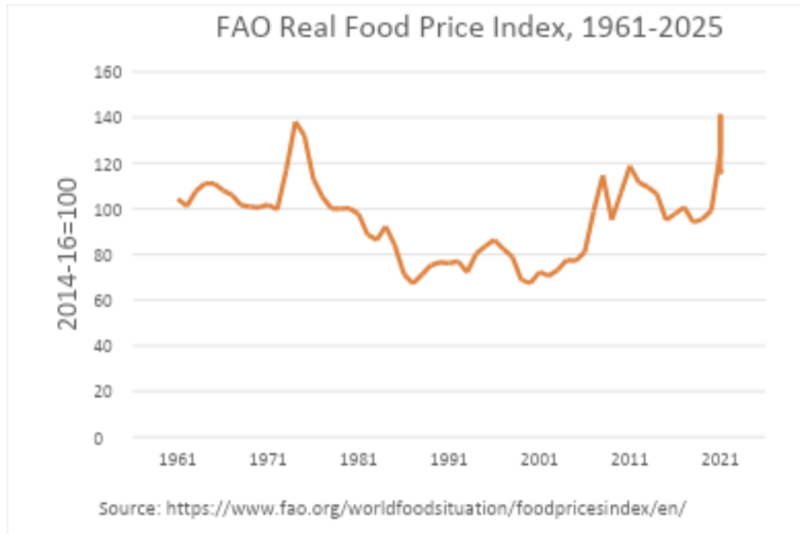

World agriculture is in rude health, easily accommodating our growing population, in spite of large shocks to trade routes. The world food prices that peaked in early 2022 have fallen back to levels seen (in real terms) in 1973, whilst per-person real incomes have risen over 250% since 1970. That is amazingly good news, driven essentially by an abundance of spare agricultural land that can and will be cultivated when food prices rise. The untapped potential of land not under cultivation has risen over time, as yields have risen and climates have become more favourable for growing. Canada, Central Asia, Brazil, and elsewhere still have enormous spare agricultural capacity.

Increases in yields since the early 1960s have resulted in 18.1 million square kilometres of cultivable land being left idle by 2023. Increased agricultural production has been a global phenomenon for the last 40 years, though the increase is slowing down. One factor driving this has been new technologies, including new crops and new farming methods. Another driving factor is more CO2 in the air, courtesy of massive and increasing fossil fuel burning. The good news, therefore, is that humanity is not remotely in danger of producing inadequate food for itself any time in the next 50 years. We can confidently predict that food will remain cheap and abundant over the coming century.

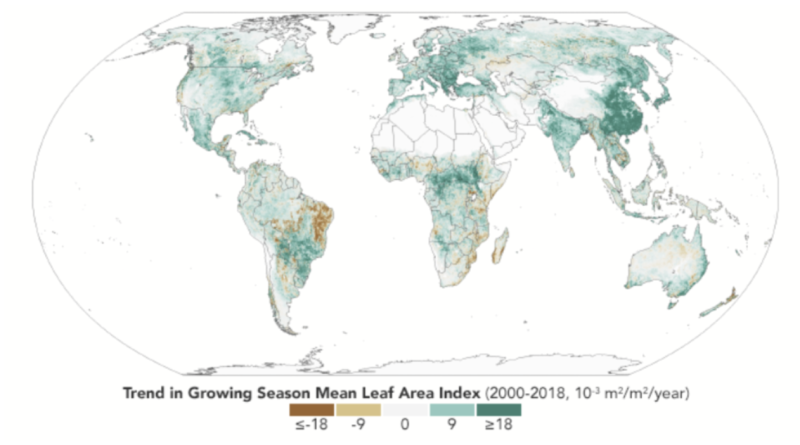

Globally, nature is thriving in terms of leaf coverage and raw local diversity. Tree rings and leaf coverage are up almost 40% globally, tracing a near-continuous upwards line over the last 50 years. This global greening is, again, the gift of fossil fuel usage, which has released fertilising CO2 from its geological depths. As shown in the map below, the greening dividend has been highest in China, India, and Europe, which is where half of humanity lives and grows food. Barring political intervention, humans will dig up a lot more fossil fuels in the coming 50 years, so this positive trend should also be expected to continue: we will see more plants and more animals.

Even the deserts are greening, thanks to the extra CO2 and extra rain. So ‘nature’ as a reasonable person would define it is going very well and with little realistic endangerment on the horizon, except of course if you choose to define ‘nature’ as the specific types of living things that were around 50 years ago, because that definition allows/compels you to claim that all change is bad, even if that change is to have more living things (i.e., more nature).

Water desalination, solar power generation, and small nuclear power generation have all become a lot cheaper over the last 20 years and look set to continue to become even cheaper. This is great news for humanity as a whole, because it means our energy-intensive way of life can likely continue indefinitely, even if the fossil fuels were to run out. Cheaper desalination furthermore guarantees that coastal cities are no longer reliant on rainwater or rivers for their water needs, making them more sustainable and independent. Better yet, the combination of cheap water and energy promises the ability to fertilise desert inlands in Australia, Arabia, and other places, unlocking yet more of the natural potential of the Earth.

The poorer regions of the world are catching up with the richer regions in terms of living standards and basic education levels, which in turn reduces their fertility levels. As a result, the runaway global population we were invited to worry about as children is no longer a realistic worry. Despite a recent reduction in life expectancy in some regions due to lockdowns and Covid vaccines, humanity as a whole is still on a longer-term trajectory of living longer and getting healthier.

New geopolitical power blocs are forming that provide a counterweight to the US and the West, promising a more balanced future wherein no country or bloc of countries can boss the rest of the world around. While the transition phase toward that longer-term balance is fraught with dangers, the longer-term political picture looks navigable.

In sum, the world is more fertile and the basic conditions for human thriving (water, food, energy, and power balance) are looking favourable. Put in perspective, the worries of our generation (fascism, neo-feudalism, nuclear wars, totalitarianism) would seem but blips towards a bright future, just as WWI and WWII proved little more than local skirmishes in the longer-run forward striding of humanity as a whole.

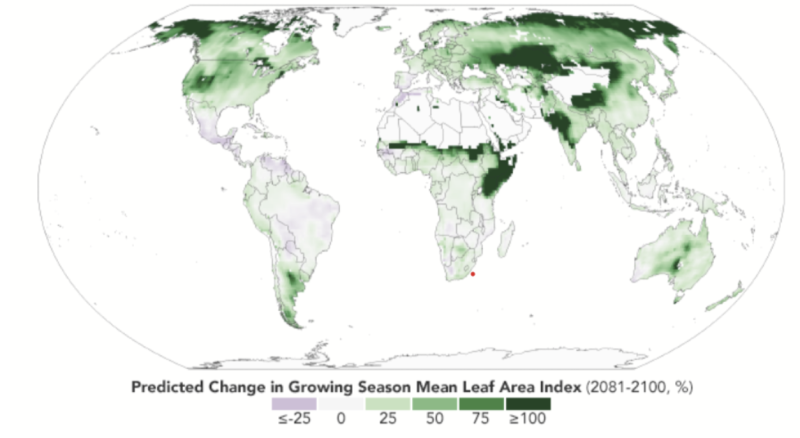

Over the next 80 years, what do we expect? Consider the growth predicted for leaf coverage, which is shorthand for ‘food and diversity abundance,’ from 2081 to 2100:

Large areas of the world, including the most populous ones, are predicted to double their plant life over the next 80 years. Every human who steps into a car or plane with a combustion engine is contributing to this future.

On the scale of humanity as a whole, we have done great and we are still looking good for at least as long as the lifetimes of our children. Even the last 5 years saw net progress: the destruction caused by lockdowns and Covid vaccines does not take away from the upward trajectory of the number and longevity of all humans on the planet.

We estimate that something on the order of 60 million people needlessly died or were prevented from being born because of lockdowns and vaccines, but some 400 million new humans were born anyway in the last 5 years, increasing the world’s population by about 200 million. Incomes and consumption even increased in poorer regions, like India and Southeast Asia.

Wars would have to be far worse than WWII to make a dent on these broad positive trends. They would have to be worse than a minor nuclear exchange. The current conflicts in Ukraine, Palestine, and elsewhere are just not deadly enough to be noticeable at the world level. While every death is tragic, humanity as a whole will continue to thrive in spite of present conflicts.

The world as a whole is doing fine, in sum. To widen our smile, let us name and acknowledge five Great Accomplishments of the West that we are honestly proud of, and feel honoured to cherish and defend in these times.

- The brilliant invention of the separation of powers. Everywhere in the West, you see the belief – and sometimes the practice – of a separation of powers. No other culture hit upon this idea, and powerful people everywhere hate it because it limits them, which is why it is so infrequently practiced. Despite being universally hated by powerful people and quite absent de facto from most of the West today, the idea is alive and well. Everyone in the West seems to believe in it in their hearts. It is in all our books on the benefits of democracy, and in all the stories we tell ourselves and our children about how our modern societies function. After the current round of neo-feudalism by those in power is over, we expect this idea to be implemented once again: the West will return to pitting groups of powerful people against each other as the winning method for keeping the powerful in check. Incidentally, we think that this idea should be taken further: that national power should be split into four rather than three parts. An active citizenry is needed to keep the executive, the legislative, and the judiciary de facto separated and informed. Rather than the corporate media as a viable “fourth estate,” we see active citizens as the fourth power needed to keep the other three powers apart by appointing top public-sector officials and judges, through a citizen jury system. This fourth power of citizens should also become what modern media companies are not, by providing the population with citizen-gathered information to keep the citizenry and the three other powers independently informed.

- Hitting upon the huge gains available from investments in, and harvesting of, diversity in science, markets, and large organisations. The great trick of the human body is to harvest the efforts of thousands of different species in our bodies without having the body overwhelmed. We use other species to digest food, keep our skin supple, optimise our teeth and internal lubricants, and so forth. The West has hit upon the same trick in its methods of societal organisation, via competitive markets wherein different people and their organisations go in totally different directions, finding out experimentally who has the better ideas that benefit all of society. Western scientific knowledge too has come from lots of scientists trying different things, with the users of science slowly (often painfully slowly, as in, over many decades) finding out who was less wrong than whom. Large Western organisations sow and harvest diversity within themselves too, via functional divisions, R&D units that stimulate diversity, and an internal tolerance for experimentation by many managers who draw on the resources of the whole.

- The universality of Western artistic expression. Today’s woke, self-obsessive norms notwithstanding, top art in the West openly tries to step away from the present and the local and speak to humanity as a whole. We do this in music, sculptures, paintings, architecture, poetry, and books. To be fair, Buddhism also tries to do this, and much of the rest of the world does this in some of its artistic forms (most often in architecture and sculptures, and sometimes in great epic stories) but the West has made it an artistic philosophy to aspire to step out of “here today” and speak to everyone, everywhere, across time.

- The offer of grace. The great gift of Christianity to the West has been the idea of grace, inclusive of mercy and benign tolerance for human ‘weaknesses.’ Most other cultures and even some strands of Christianity do not adopt this forgiving, compassionate attitude. The true humanistic perspective in which we lovingly embrace our own natures and our mortal enemies as simply human – warts and all – is not only kind, but offers people the emotional security needed for self-love, honest self-reflection, development, and self-improvement.

- The creation of public spaces where the heart and the mind can speak. From village squares to town markets; from happy hour after work to parent night at school; from museums of art to public footpaths in the city centres; from interruption microphones at conferences to debating societies in academia: Western people consciously create space for citizens to speak their minds and display their hearts. As with the separation of powers, the present weakness of implementation of this phenomenon does not diminish the continued potency of the idea. Abusers of power often shut down public spaces to prevent open dissent, but the idea that we should have such spaces is alive and well in the West. Even the totalitarians in charge know that their intolerance has taken over and hope for a future in which the open spaces are again truly open (i.e., once everyone agrees with them, out of their own volition naturally!).

Of course, the West is no stranger to all the ills of humanity, from industrialised murder of the enemy to institutionalised oppression of its own population. Of course, Western culture and institutions owe a huge debt to non-Western cultures, with contributions ranging from the Chinese idea of a meritocratic bureaucracy to the useful plants of the Andes (potatoes, cacao, corn, etc.).

Of course non-Western cultures have their own beautiful distinguishing traits, like the penchant of the Chinese to value social harmony above all, and the notion of lotus-like morality (a shining flower amidst the muck) in India. Of course there is great diversity within the West, from the dour Lutherans of the North to the ruthlessly selfish of the ultra-West, and not all incarnations of Western life display all of the great five accomplishments in equal measure.

Still, we encounter the fruits of all five in every Western country, and far less of them anywhere else. Outside the West, there are few public spaces to be seen and heard in, little grace towards our true nature and that of our neighbours, little in the way of universal art that speaks to us all and thereby reminds us of our common struggles in this world, little investment in and harvesting of diversity, and no true belief in the separation of powers that motivates power-sharing.

It is because of the benefits available from the five accomplishments above that the rest of the world migrates to the West and stays there, while few Westerners opt to live outside of the West unless those places are themselves more Westernised, like Hong Kong was for a while. These five elements define what it means to be of the West: stunning historical accomplishments to cherish, to nurture, and to expand in our hearts and minds.

The West is great because it has successfully charted a path of inherent tension that acknowledges, yet separates, two core ingredients needed for human thriving that appear to be in conflict. The first is a brutally honest intellect that determines how things actually work and is realistic about the corrupting influence of power. The second is acceptance of human nature and allowing that nature to spill out into open places where soothing lies, beauty, and ideas can be shared with one another. To this point in history, these unlikely bedfellows of cold reason and warm love have shown themselves to be an unbeatable combination for producing human thriving.