It has been four years since the world was saved, or not, by miraculous Covid mRNA vaccines.

It has also been several years since my first letter on the topic was rejected by an editor of a biomedical journal. And my case series of rejected letters on Covid vaccines keeps expanding. The score is now 5:0. The last rejection recently came from the editor of the Journal of Infection, where “Each issue [also] brings you…a lively correspondence section.” My lifeless letter referred to a study of the healthy vaccinee bias in Austria.

Is my case series large enough to infer causality? Perhaps it is. Of course, the common cause could have been poor-quality science. May I offer, perhaps, one refuting observation? My second letter (rejected by The Lancet) would have exposed in 2021 what Høeg et al. exposed in 2023 in a letter that somehow got into The New England Journal of Medicine. A careless editor, I think. Maybe he or she is no longer an editor.

I am sure that my fifth rejected letter was just another badly written text with no scientific merit. For sure it had nothing to do with the possibility that the letter, along with the authors’ response, might have led to disturbing findings. So, let me share my letter here. You will be the judge again: worthy or meritless?

To make it more interesting, I will include an analysis that was mentioned in the letter (without my revealing the scary result). It was not difficult to compute, however. The paper shows evidence of vaccine-related deaths—from Covid—within two weeks of an injection in people who were previously infected. Or let me state it more conservatively: The evidence is at least as good as the paper’s evidence for vaccine effectiveness against Covid death in fall 2021.

The Letter

May 15, 2025

Journal of Infection

To the Editor:

Riedmann et al. report a thoughtful, comprehensive analysis of the healthy vaccinee phenomenon in Austria, which included a novel approach.1 Unvaccinated were matched to vaccinated on several variables, and the authors compared several outcomes over two weeks after the completion of various doses. Table 3 (article) and Tables S44-S45 (supplementary document) show results for all-cause mortality, non-COVID-19 mortality, and COVID-19 mortality.

Since the healthy vaccinee bias diminishes over time, it would be interesting to extend the analysis of the matched cohorts to 4 weeks and 8 weeks. Numerous studies have estimated effectiveness over one to two months post-vaccination, which sometimes coincided with the duration of a COVID-19 wave.

The authors mention a rudimentary method of correction, derived from the idea of prior event rate ratio adjustment.2-5 The hazard ratio of COVID-19 mortality is divided by the hazard ratio of non-COVID-19 mortality. Although not perfect, it may provide more insight when follow-up is extended, and the number of COVID-19 deaths is larger. Applying the method for 19 COVID-19 deaths (Table 3, complete primary vaccination) is still good enough to remove the bias. After the rudimentary correction, the ratio is no longer below 1, whether hazard ratios or rate ratios are used.

On another note, it seems that rate ratios in Tables S44-S45 were mislabeled as hazard ratios and adjusted hazard ratios.

Sincerely,

Eyal Shahar, MD, MPH

Professor Emeritus

University of Arizona

References:

- Riedmann U, Chalupka A, Richter L, et al. Underlying health biases in previously-infected SARS-CoV-2 vaccination recipients: A cohort study. Journal of Infection, Volume 90, Issue 6, 2025, 106497, ISSN 0163-4453, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinf.2025.106497

- Tannen RL, Weiner MG, Xie D. Replicated studies of two randomized trials of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors: further empiric validation of the ‘prior event rate ratio’ to adjust for unmeasured confounding by indication. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2008 Jul;17(7):671-85. doi: 10.1002/pds.1584. PMID: 18327852

- Pálinkás A, Sándor J. Effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccination in preventing all-cause mortality among adults during the third wave of the epidemic in Hungary: Nationwide retrospective cohort study. Vaccines (Basel). 2022 Jun 24;10(7):1009. doi: 10.3390/vaccines10071009. PMID: 35891173; PMCID: PMC9319484.

- Atanasov V, Barreto N, Whittle J, et al. Understanding COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness against death using a novel measure: COVID excess mortality percentage. Vaccines (Basel). 2023 Feb 7;11(2):379. doi: 10.3390/vaccines11020379. PMID: 36851256; PMCID: PMC9959409.

- Shahar E. On methods to remove the healthy vaccinee bias. In: Topics in Epidemiology and Statistics. Amazon Kindle Ebooks (2025)

The Rejection

Two days later, a message with boilerplate text landed in my inbox.

Manuscript Number: YJINF-D-25-00940

Article Title: Letter to the Editor

Corresponding Author: Professor Emeritus Eyal Shahar

Submitted to: Journal of Infection

Dear Professor Emeritus Shahar,

Many thanks for submitting your manuscript to the Journal of Infection. Unfortunately we receive many more papers than we have space to publish and we can therefore process a finite number of submissions. Unfortunately, after consideration by the editors, this paper did not achieve sufficient priority. Please note we do not encourage resubmission of a paper with a reject decision.

I am sorry about this adverse decision and that we cannot provide more specific reasons for rejection, and I hope you will continue to submit your work to the Journal of Infection in the future.

Yours sincerely,

Professor Robert Charles Read

Editor

Journal of Infection

I was mildly surprised. Interestingly, the boilerplate text was written for rejected manuscripts (papers). Don’t they have comparable text for rejected letters? How often are letters rejected by this journal? Your guess is as good as mine. Perhaps it is even similar to mine.

Analysis

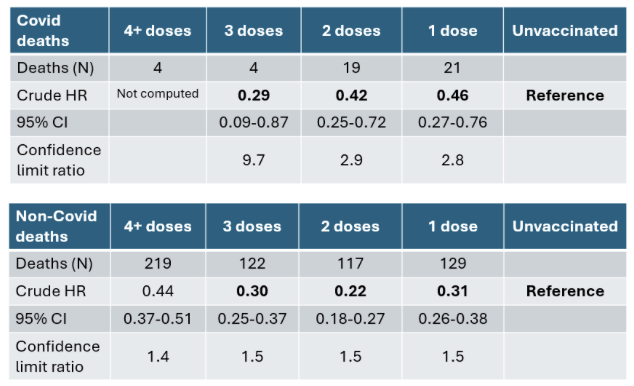

The numbers below were transcribed from Table 3 in the article (version 2, corrected). These are the data and results to which my letter refers. The confidence limit ratio was added (my computation). I will write more on this statistical index later, but the smaller the number, the better the estimated hazard ratio (HR).

Tables. Hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for Covid and non-Covid mortality according to the number of vaccine doses in the two weeks after vaccination. Controls (unvaccinated in that time window) were matched to each group of vaccinated people on age group, gender, and nursing home residency.

The hazard ratios of death came from matched cohorts, so confounding by age, gender, and nursing home residency was removed. The unvaccinated were also matched on the vaccination date, so confounding by time trends was avoided. The remaining confounding is the healthy vaccinee phenomenon. Vaccinated people are healthier, on average, than their unvaccinated counterparts, and therefore, their Covid mortality is expected to be lower even if they were injected with a placebo. You can see that their risk of death from non-Covid causes was lower (hazard ratios < 1). That’s because they were healthier, not because Covid vaccines are a panacea. The healthy vaccinee phenomenon appears to be universal. It does not disappear after two weeks.

However, the authors did not select die-hard unvaccinated. They write: “The unvaccinated control group had no documented vaccinations up to 14 days after the relevant matched vaccination day.”

Which means that the healthy vaccinee bias was estimated against a group that included people who were vaccinated later. The true bias might have been larger.

Back to the tables above.

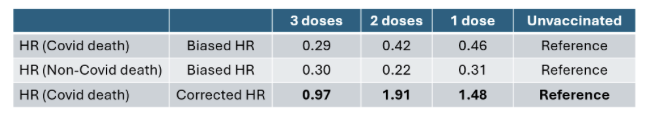

All the hazard ratios of Covid death are smaller than 1, and they are all biased. No benefit is expected in that time window (two weeks). As I wrote in my letter and elsewhere, there is a method to remove the bias, which is not perfect but is better than no correction at all. Divide the hazard ratio of Covid death by the hazard ratio of non-Covid death.

In this case, if the result is about 1, the bias was removed. If it is still below 1, the bias was not fully removed. If it is above 1, we should be worried. Are we observing an increased risk of death that was obscured by the healthy vaccinee bias?

The results are shown in the table.

After the correction, the hazard ratios of Covid death within two weeks of the first and second injection are 1.48 and 1.91, respectively.

Is this the truth? Possibly. The immediate post-vaccination period is risky for infection and death. I have seen it in data from Israel, Denmark, and Sweden. Others have also written about this.

As for the third injection (0.29/0.30=0.97), I can offer two competing explanations:

The first one is short. Those unfortunate vaccinated people who were susceptible have died after one or two doses. No susceptible people remained among those who have reached the third dose.

The second explanation is long. The estimated hazard ratio for Covid death (0.29) is poor. It is based on only four events. How do we know how poor it is, say, as compared with the estimates for two doses and one dose? We compute an index called the confidence limit ratio: the upper bound divided by the lower bound. The ratio is 9.7 for three-dose recipients versus 2.9 (two doses) and 2.8 (one dose).

If you compute the confidence limit ratio from many studies, as I have done over the years, you will find out that reasonable-size studies generate a ratio around 2, and small-size studies (few events) generate ratios north of 5. Close to 10 is what you get when the inference is derived from four events in one category. Most importantly, the merit of an estimate is inversely related to the confidence limit ratio, not to “statistical significance.” I will explain why shortly.

Billions have been vaccinated, and we try to draw inference from 19 events and 21 events because one paper after another excluded data from the early post-vaccination period.

Moreover, extended follow-up of the matched cohorts can provide unique insight into true vaccine effectiveness because the unvaccinated were matched on the vaccination date. (Vaccination campaigns often coincided with Covid waves, which led to confounding.) The authors have a nearly perfect research setting: large cohorts, matching on key variables, and data on non-Covid deaths that allow basic correction of the healthy vaccinee bias. But we are unlikely to see the data because my letter had no merit. Maybe another letter will bring this up and get accepted. Or maybe not.

Let me restate my conservative statement at the beginning:

The evidence I show here is at least as good as the evidence for vaccine effectiveness against Covid death in fall 2021.

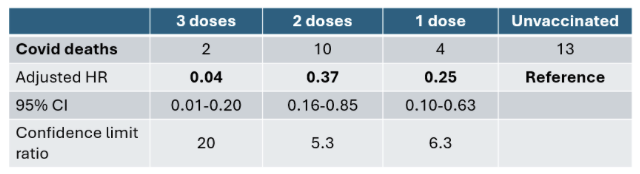

The numbers below were transcribed from Table 2 in the article (version 2, corrected). The confidence limit ratio was added (my computation).

As you can see, the number of Covid deaths is smaller than in the matched cohorts, and the confidence limit ratios are substantially larger. The confidence limit ratio for three doses breaks records (20).

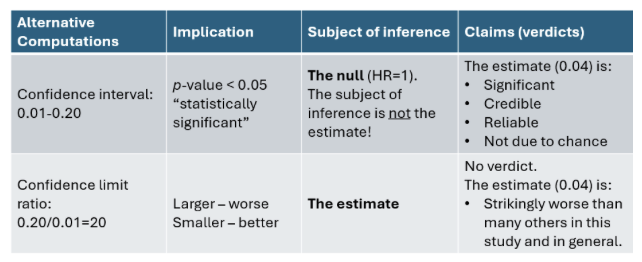

I can hear the authors and readers: “But all the estimates above are statistically significant. The upper bound of the confidence interval is below 1, which implies p-value < 0.05.”

Indeed. However, “statistically significant” is not what you probably think it is.

It is not about the quality of the estimate.

A crash course (for those who are interested in statistics and linguistics)

My example is taken from 3 doses (table above): HR (95% CI): 0.04 (0.01-0.20). The estimate (0.04) is highly statistically significant.

All the claims (verdicts) in the first row of the table are false—indisputably false. They are derived from an unfortunate, entrenched misinterpretation of “statistically significant,” which has historical-linguistic roots.

When the term was coined many years ago, the adjective “significant” had a different meaning. In late-19th-century English, it meant that the estimate signified (showed) evidence against the null. The phrase did not refer to any intrinsic quality of the estimate. Over the years, the contemporary meaning of the word “significant” has replaced the original meaning, mistakenly attributing qualities to the estimate itself (significant, credible, reliable, unlikely to be due to chance).

None of these interpretations has any basis in the statistical test. It is wishful thinking. Rejection of the null hypothesis is based on the estimate (through a test statistic); it does not endow the estimate with any credibility. If we wish to learn about randomness-related qualities of an estimate, we need to rely on the standard error alone, and the confidence limit ratio is trivial math on the standard error. The closer it is to 1, the better the estimate. An astute epidemiologist proposed this index many years ago, but sometimes novel and valid ideas stay dormant for a long time.

You may read the linguistic story in the book The Lady Tasting Tea: How Statistics Revolutionized Science in the Twentieth Century by David Salsburg. One paragraph on page 98 is an eye-opener.

Epilogue

There is a lot more to write on that paper that includes 72 pages of supplementary analysis; some of it was “requested during the review process.” I can imagine the battle with hostile reviewers when the topic is the healthy vaccinee bias.

I already have about 100 rows of data and analysis in an Excel file. (Preview: the third dose was useless, and more doses might have been worse.) Should I send a manuscript to Professor Read, who had hoped that I would continue to submit my work to the Journal of Infection?

Let me think about it.