Changing the direction of a dinosaur was, presumably, hard for any who tried. Especially when the direction of the dinosaur was highly profitable to its minders. While paleontology does not fully support the analogy, the picture describes the new Global Health Strategy just released by the US government. Someone is trying hard to return the dinosaur – the largest source of funding for international public health there is – back toward a path that addresses healthcare and real diseases. Someone else wants to keep it steered on the path preferred by the World Health Organization (WHO), Gavi, CEPI, and the corporate industrial complex that has co-opted public health. Both are trying to look like ‘America First.’

Within all this, a thread emerges that does seem to be pushing for a more stable, healthier world. The hope is that the strategy document’s confusion just reflects an underlying transition, and the glimpses of a return to common sense and good policy will become more obvious as it is implemented.

The strategy has three pillars, which read as if written by people with very different ideas. The first attempts to claw back what the pandemic industry lost when the US administration defunded the WHO and Gavi. The second aligns with the US HSS stated approach of evidence-based policy and reduced centralization (i.e. good public health). The third plugs (not unreasonably) for US manufacturing, and its future really depends on which of the first two pillars is doing the administration’s bidding.

Pillar One: Supporting the Pandemic Industrial Complex

Pillar One, ‘Making America Safer,’ deals with outbreak risk and essentially reiterates the talking points of the WHO, Gavi, and CEPI, which the current US administration has been defunding. Whilst the White House is telling us that Covid-19 was almost certainly the result of a lab leak after reckless gain-of-function research (a logical assumption), the strategy document would have the US public believe that pandemics of natural origin (within which they still include Covid) pose an existential threat to Americans in America, and that the US has stopped “thousands” of such outbreaks in recent years.

Ebola. COVID-19. Swine Flu. Zika. The world has experienced multiple epidemics and pandemics in the 21st century, and the threat of a future pandemic is increasing with global connectivity amongst humans and between humans and animals at an all-time high.

This is massively disappointing to read in a serious document. Global data indicates that mortality, and probably outbreak frequency, declined for the decade pre-Covid as infectious disease mortality has generally. The last major mortality outbreak likely of natural origin, the Spanish flu, was in the pre-antibiotic era over a century ago. Medical technology has progressed since then, not just propaganda.

We are better at detecting and distinguishing epidemics from the background of disease because we invented PCR, point of care antigen and serology tests, gene sequencing, and digital communications. Much of this came from America, but is here being used against it to purloin more resources on the pretext that if we lacked the technology to detect a pathogen previously, then the pathogen could not have existed. Does anyone seriously believe that a hundred years of technological development, improved living conditions, and wildlife eradication actually leaves us more vulnerable?

A return to this poorly-evidenced pandemic rhetoric is a win for the pandemic industrial complex and those who see a need to continue what the strategy document calls elsewhere “perverse incentives to self-perpetuate rather than work towards turning functions over to local governments.”

The strategy plans to detect outbreaks within seven days, and will staff countries considered to be high risk for this purpose. This is where logic breaks down. If Covid is indeed a product of gain-of-function research, then the focus should be on countries allowing reckless laboratory manipulation of viruses. However, Pillar One envisions staffing low-income countries in sub-Saharan Africa and Asia, perpetuating the probable fallacy of increasing risk from zoonotic spillover (pathogens jumping from animals to humans):

Every year, there are hundreds of concerning infectious disease outbreaks around the world, including outbreaks of Ebola, mpox, and highly pathogenic strains of influenza. The African continent alone had more than 100 outbreaks in 2024.

Pillar Two: Addressing Disease and Life Expectancy

The second pillar, “Making America Stronger,” assumes (reasonably) that America will be better off if the world is generally less sick and correspondingly more economically stable. This continues previous, evidence-based understandings of the role of public health, where the largest remediable disease burdens are the recipients of the most resources – namely malaria, tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS, and polio (which is a long-running international effort that needs to be brought to a conclusion).

Missing is any mention of the major drivers of good health and longevity – the reasons why people in wealthier countries started living longer a century ago – nutrition, sanitation, and better living conditions – but there is at least a discussion of the role of economies in achieving these. Importantly, attention is paid to health system strengthening, which is essential if there is to be a transition from recipient status to self-sufficiency:

…the United States often chose to invest in directly building health delivery capabilities, often minimally connected to national health systems…[These] too often resulted in parallel procurement systems, parallel supply chains, program-specific healthcare workers, and program-specific data systems.

Countries need to do their own implementation if US aid is not to be flowing forever.

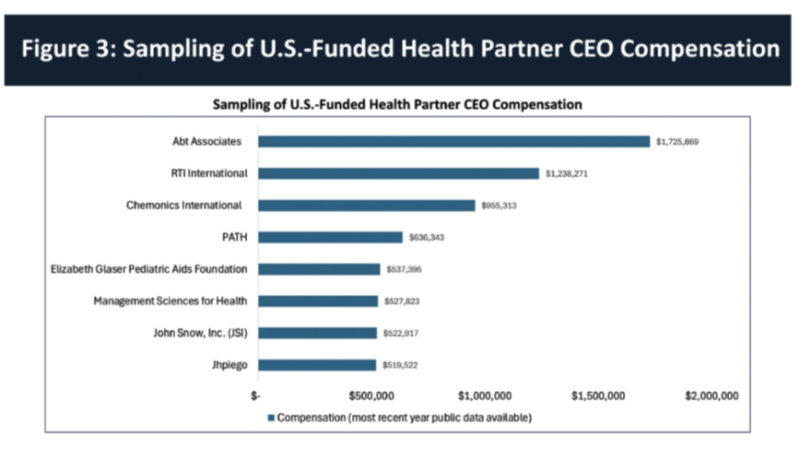

A graphic from the Strategy, showing CEO salaries from some of the major agencies that have managed US health aid for the past couple of decades, gives an idea of the problem that the US administration must address. There is simply no justification for individuals to receive multiples of the US President’s salary to distribute US aid to poor people. It is not just CEOs. Other senior executives in US-funded NGOs and foundations can also take home several hundred thousand per year, and whole new campuses have been built in Geneva, one of the most expensive cities on earth, to house their staff.

These CEOs’ industrial-scale salaries reflect the returns they are expected to realize. You don’t pay over a million dollars per year to someone to improve clinic access in Burkina Faso or support health workers in Malawi. You pay such salaries because you expect they will bring in big money for your organization’s survival and expansion.

Regarding the impact of such salaries on value for money to the US taxpayer:

A recent analysis by the Kaiser Family Foundation and Boston University found that these technical assistance, program management, and overhead costs are negatively correlated with improvements in health outcomes,

Together with improved underlying conditions, investment in national systems rather than external executives would provide an exit strategy for future administrations (malaria, tuberculosis, and HIV/AIDS are all predominantly diseases of poverty). Good public health.

Pillar Three: Aiming for Independence or Dependency?

Pillar Three, ‘Making America more Prosperous,’ emphasizes US-based manufacture of health commodities such as diagnostics, medicines, and vaccines for the rest of the world to use. This smells of a concession to the make-in-America lobby – not in itself a bad thing – but sits well with the first pillar (surveil, sow fear, lock down, mass vaccinate, and concentrate wealth that we saw in Covid) and poorly with the idea of building capacity and self-reliance in recipient countries so that the US taxpayer is not forever on the hook.

Throughout the strategy, we hear of the efficiencies of bilateral approaches – the US will work directly with recipient country governments as much as possible, reducing reliance on the wealthy international bureaucracies that absorb so much funding intended for other people. This is consistent with the US administration’s approach in leaving the WHO and defunding Gavi, and promises actual capacity building essential for an exit strategy (which the current system of expanding centralized agencies works against). However, there is no mention of the downside and how this will be managed – the US will find itself funding parallel programs to other donors, resulting in duplication and multiplying reporting requirements. More experienced strategists would have addressed this – it is hoped that this can be achieved without repeating the mistakes of the past.

A Step Forward, but not yet out of the Mud

If the underlying driver of the new US global health strategy is to build capacity within recipient countries towards self-sufficiency, reducing or removing the burden on US citizens, then all will win from this approach. Such an outcome will also require fair and mutually beneficial trade to ensure economies grow, which the third pillar here does not discuss. Policies are needed that do not start or support wars and foment large-scale disorder, and are based on sound public health rather than profit.

Implementation of direct government support will also require a willingness to swallow some missteps by recipient countries in building self-reliance – we have accepted gross missteps from our ever-growing international bureaucracies, so this should not be an impediment.

If an underlying driver is also to perpetuate the falsifying pandemic risk to ensure profit and wealth concentration for large Pharma and biotech companies, then Pillar One sets a good basis, and Pillar Three can be seen in that context. In this case, the US should rejoin the WHO and the broader pandemic industrial complex, enjoy the feeding frenzy while it lasts, and accept that global health in general will continue to slide.

Given the emphasis of the current administration on increased transparency and the role of evidence in domestic public health, against the preference of very powerful lobbies, a return to a solid evidence-based approach seems to be intended. The idea of building integrated domestic capacity so that countries can take over their own healthcare is commendable, commonsense, and aligns with the WHO and Gavi withdrawal. The stated commitment to keep overall funding at current levels for existing commitments should address concerns regarding short-term harms arising during the period of change.

The overall intent of the US global health strategy seems good – it just reads as if not all their writers and strategists are on board with it. If it is to work, a more cohesive approach will be needed, and some preparation for the obvious pitfalls it is going to encounter.