Alot has been written on the global food system—its industrialisation, ecological consequences and the erosion of cultural, economic and food sovereignty. Despite this onslaught, however, traditional rhythms and communal resilience persist in the countryside, especially in countries like India. Cultural practices continue to foster a sense of rootedness. What’s more, this is also reflected in the back lanes of towns and cities.

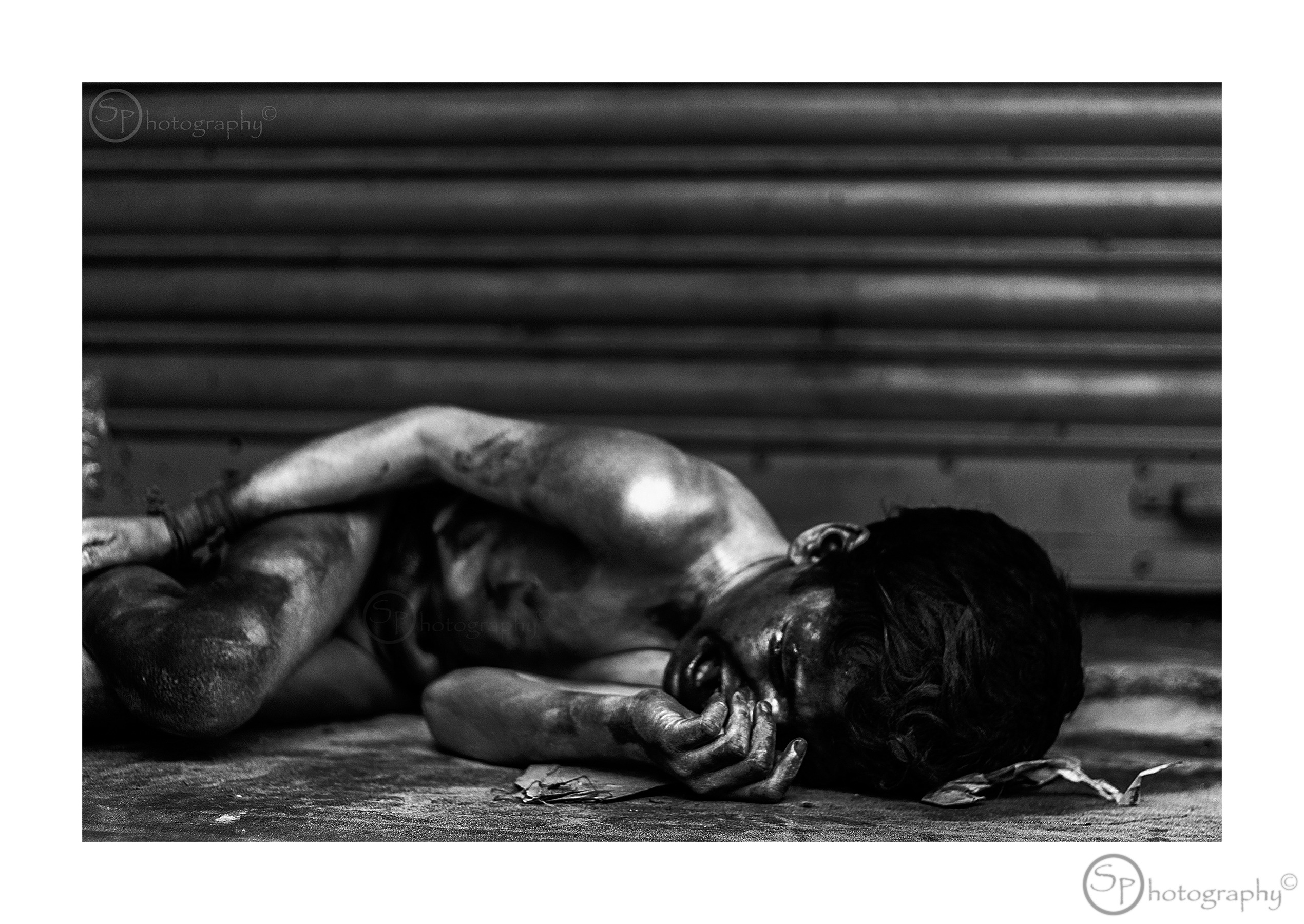

Life in the Lanes Documenting Chennai is an open-access e-book that uses visual-based storytelling via low-res street photography. It conveys a narrative about the endurance of communal life and sacred practice amid the everyday pressures to be found in modern urban settings.

When walking the cramped, noisy lanes of the Sowcarpet area of Chennai (South India), the interweaving of commerce, everyday survival and spirituality is striking. A phenomenon that resists the tendency to compartmentalise life into discrete spheres of ‘work’ and ‘faith,’ ‘secular’ and ‘sacred.’

In this packed area of Chennai, the sacred spills out of temple walls and into marketplaces, shops and alleyways. While societal structures may evolve externally, fundamental cultural and spiritual values remain deeply entrenched. Indian urbanism allows for the coexistence of age-old practices (that often have their roots in rural India) with contemporary realities. Shrines rest beside fruit stalls and ritual objects like conch shells, limes and leaves adorn streetside businesses that engage in modern commerce.

These items are religious symbols that serve as markers of cultural identity. For instance, the portrayal of Hindu deities on everyday items like bags of rice reinforces cultural connections within modern contexts. Such representations often feature vibrant artistic styles that blend functionality with cultural significance.

It is a spirituality that permeates the lives of the working-class communities who inhabit these urban spaces, helping to sustain personal and community identity and resilience.

What is observed in the lanes of Sowcarpet resonates with some of the themes explored in agrarian writings that note how ancient agricultural societies—from pre-Christian European to Norse and Hindu cultures—regarded farming as a sacred vocation. The soil was alive, and the cycles of planting, growth, harvest and fallow embodied the deepest rhythms of life, death and regeneration.

In the Norse worldview, this was echoed in seasonal rituals honouring gods such as Freyr, linked to fertility and good harvests, while Hindu traditions speak of Bhumi Devi, the earth goddess and the principle of seva—selfless service—which frames labour as an act of devotion.

Agrarian philosophy, too, especially that of Wendel Berry, talks about the unity of land, people and cosmos, affirming that right livelihood stems from harmony with natural cycles.

For millennia, deities governed rain and fertility, and communities came together in festivals aligned with solstices and harvests to honour these cycles. Agriculture was more than an economic act. It was a gift exchange with the earth that cultivated gratitude, stewardship and communal solidarity.

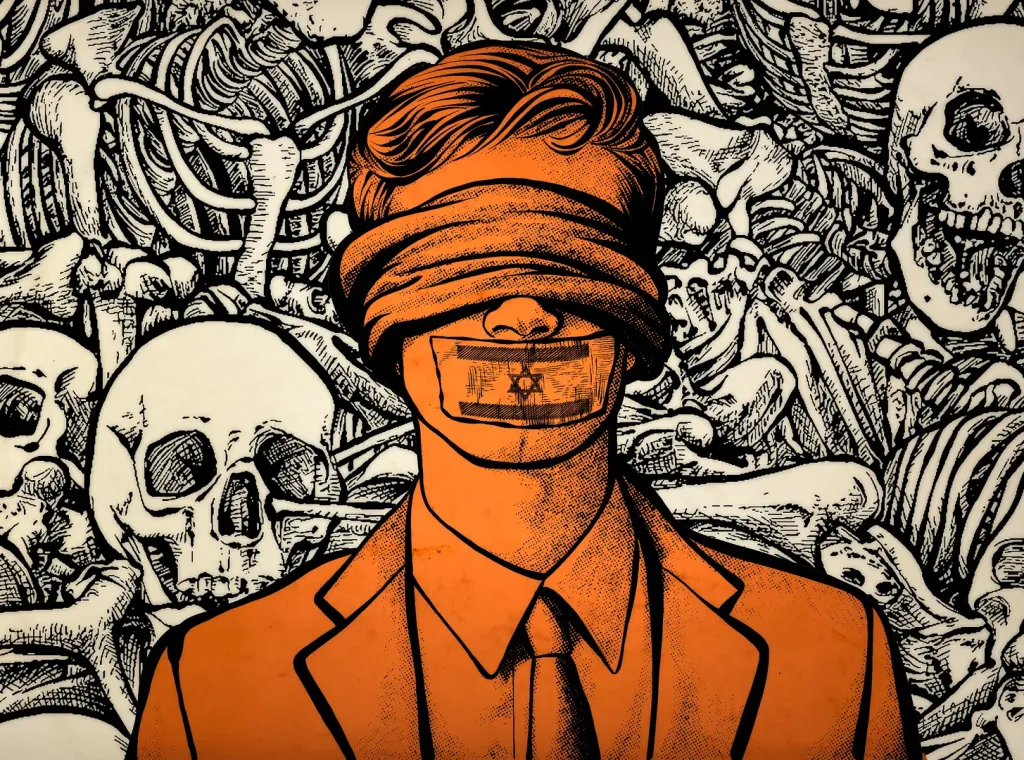

Much of this has been lost due to the advancement of industrial agriculture and corporate control. Monocultures and mechanisation have uprooted these cyclical relationships, transforming food production into a depersonalised, profit-driven business that destroys or undermines human health, ecological balance and cultural continuity. The results are stark—dispossession, loss of local food sovereignty, environmental degradation and social fragmentation.

Although in Chennai’s urban lanes, the contexts differ—rural fields versus urban alleys—the spiritual element remains strikingly similar. In both, labour and life are imbued with meaning beyond the economic. Whether a farmer tending the soil or a street vendor arranging produce, these workers act within a framework underpinned by a larger cosmic and social order.

The concept of dharma reverberates across the landscape: duty, righteousness and interconnectedness that tie individual actions to the wellbeing of community and environment. Many dharmic traditions emphasise the significance of seva (selfless service), with charitable giving—known as dana in Sanskrit—considered an essential aspect of one’s dharma or religious duty. This practice is perceived not merely as a moral obligation but as a spiritual endeavour that fosters personal growth and good karma.

Communities rely on deep-rooted beliefs and cultural practices that resist the homogenising forces of neoliberalism, capitalist commodification and a narrow consumerist mindset. The artistic kolam patterns drawn by women at entrances, the temple festivals amid urban chaos and the small acts of care, giving and devotion assert spiritual sovereignty and communal belonging.

Such persistence mirrors the seasonal rites of rural life and the earth-honouring rituals preserved in agrarian thought—all of which express a shared understanding that human thriving can only be secured through reciprocal care with the land and with each other.

This persistence, however, is precarious. The forces that threaten rural agricultural traditions—land grabs, seed patenting and the imposition of industrial monocultures—have parallels in the urban domain through gentrification and the destruction of local neighbourhoods, the displacement of street vendors and the homogenisation of thought in an era where aspirations are increasingly shaped by the corporate media and its advertisers.

In this respect, the global market economy’s encroachment remakes both rural and urban landscapes, undermining or erasing embedded cultural rhythms and imposing a sanitised, commodified vision of modernity and ‘progress’.

For instance, take the industrial food system, driven by monocultures, chemical inputs and a singular focus on profit. This has led to a proliferation of highly processed, nutrient-deficient foods. The direct result of this shift has been a significant increase in diet-related diseases such as obesity, diabetes and cardiovascular issues. What is celebrated as economic growth—the expansion of the healthcare industry—is, in reality, a response to the negative health consequences created by another aspect of this same industrial ‘progress’.

From a purely economic standpoint, the expansion of the private healthcare sector is considered a positive development, as it contributes significantly to GDP growth. This reflects an increase in spending on medical services, pharmaceuticals and technology, thereby implying economic advancement. This form of ‘progress’ is a perverse reflection of the debasement of what was once a healthy food system based on traditional agronomic practices.

In traditional systems like Ayurveda, health was seen as a product of harmony between the individual, their diet and the natural world, underpinned by a spiritual understanding of existence. This has been supplanted by a biomedical model that views the body as a machine to be repaired, disconnected from its food source and environment.

Healthcare has become a commodified service—a business model thriving on the very illnesses created by the industrial agricultural system. It is becoming quite a well-worn statement in certain circles, but it makes it no less true: we need more family farms based on organics and fewer family doctors.

For centuries, Ayurveda offered a holistic model of health tuned to the rhythms and needs of traditional communities. Its preventive approach was remarkably effective in settings where people ate seasonal, unprocessed foods and they lived lives more closely attuned to nature. Ayurveda taught that health was the product of harmony—between body, mind, spirit, diet, community and the environment.

However, whether in the back lanes of towns and cities or out in the fields, there are complementary aspects that challenge dominant narratives of progress, which equate technological acceleration and market expansion with ‘development’.

There is a longing for rootedness—both in the land that produces healthy food and in the quest for a sense of place—with reverence for individuals, communities and the natural world.

The sacred is not a relic of an idealised past. Spirituality is enacted daily through ritual, work and community care and serves as a form of reaffirmation that sustains hope and dignity. Asserting these ways involves regenerating food sovereignty, fostering agroecological practices and respecting communal bonds rather than sweeping them aside.

It also demands recognising labour as engagement with life’s cycles and community welfare, not as alienated toil to line the pockets of shareholders who live half a world away.