By Neenah Payne

By Neenah Payne

Daring Escape from Auschwitz features the enormous courage of Rudolf Vrba (Walter Rosenberg) and Alfréd Wetzler who escaped from the Auschwitz concentration camp to warn others and saved the lives of hundreds of thousands of Jews in Budapest. Withdraw US From World Health Organization Now! shows how close Americans are to losing the freedom many of us take for granted. If the WHO Pandemic Treaty is passed, escapes like those will not be possible because there will be nowhere to go.

It’s so easy to take freedom for granted when we have it. So, perhaps now is a good time to take a look at some remarkable stories of courageous Americans who found their way to freedom against impossible odds in the 19th century and others who helped them on the famous Underground Railroad. Knowing this inspiring history in which a wide variety of Americans participated may serve as a guide for us now as we face perhaps the biggest threat to freedom humanity has ever faced.

Thomas Downing: New York’s Oyster King! explains that Thomas Downing (1791-1866) was so famous around the world in the 19thh century for his New York oysters that Queen Victoria sent him a gold watch! The life of Thomas Downing would make a thrilling film! While his restaurant served the New York elite in a fancy dining room, the upstairs and basement served as important stops on the Underground Railroad for runaway slaves. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 made it a felony to help or harbor escaping slaves and fines could be up to $1,000 — about $38,500 today. Yet, Downing ran those risks for years while police, mayors, and other government officials dined in the same building! This is a hero writ large! Talk about a very courageous double life — James Bond material!

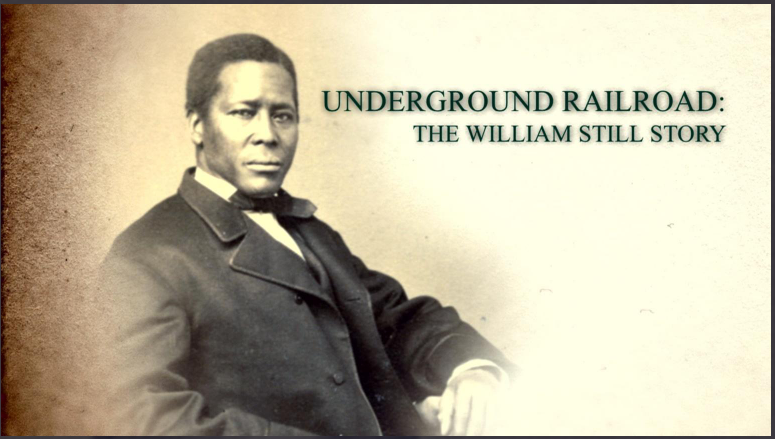

The Forgotten Father of the Underground Railroad

The author of a book about William Still unearths new details about the leading Black abolitionist—and reflects on his lost legacy.”

Illustration by Meilan Solly / Photos via Swarthmore College, Wikimedia Commons under public domain

In the more than 100 years since his death, William Still has been marginalized, sometimes even forgotten, by histories of the movements to which he contributed so much.

Peter Freedman saw danger in the unfamiliar faces around him. It was August 1850, and he had come to Philadelphia looking for parents he had not seen in decades—not since he was separated from them as a child and sold south. The journey from Alabama had been long and arduous, but now that he was here, he was unsure if he should have come. Would he even recognize his parents if he saw them? It had been more than 40 years, after all. He had good reason to be wary. Though he was now legally free, having purchased his own freedom after decades of bondage, he’d heard stories of kidnappers who were on the lookout for unsuspecting Black men like him. Some of these kidnappers even posed as abolitionists.

Upon arriving in the city, Freedman went to the boardinghouse of James Bias, a Black doctor he was told he could trust. Bias was out of town. Instead, his wife, “a bright mulatto woman, with a kind smile and a pleasant voice,” as Freedman later recalled, welcomed the visitor and arranged for a guide to help him look for his parents. The two men walked around the city, inquiring among Black men and women they met if any had known a man named Levin and his wife, Sidney, who had lost two children 40 years prior. Freedman and the guide spent two days conducting their search with no success.

At this point, Eliza Bias suggested Freedman go to the local Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society office to speak to a man named William Still who worked there and might be able to help him.

It was about 6 in the evening when Freedman set out with his guide. He had the sense that the guide did not believe his story, and this only accentuated his anxiety. When they finally reached the office, Freedman peered through the window and saw a young Black man, neatly dressed, writing at a desk.

When they entered, the young man, tall and dark-skinned with short-cropped hair and strong features, rose to greet them. Still was not yet 30. He was born free in New Jersey in 1821, the youngest of 18 children, to parents who had been enslaved, and from an early age was drawn to the antislavery struggle. In time, he would rise to prominence as a leader of the abolitionist movement, and he would continue his work on behalf of Black rights in the decades following the Civil War.

When he died in 1902, he was one of the most famous and respected Black men in America; newspapers across the country called him “the father of the Underground Railroad.” But there was perhaps no moment in his life more remarkable than this unlikely but pivotal encounter one August night with a man he had never met. It was unlikely, but no coincidence, because Still had placed himself at the center of a vast network of people who were committed to aiding fugitives from slavery in their dangerous flight north. This network was built on word of mouth, on carefully compiled records, on letters and telegraph wires, on steamship lines, railroad tracks, and country roads, all converging on Still and the Anti-Slavery Society’s Philadelphia office.

Still’s job was to ensure that fugitives moved through Philadelphia as safely and efficiently as possible. This meant coordinating with allies outside of the city, sometimes in towns just miles outside of Philadelphia, other times in Southern port cities as far away as Norfolk, Virginia. It meant making sure that when fugitives arrived in the city, they were met at the docks or the train station and guided to a safe place to stay—often the Still family home. It meant providing medical care, food, a bath and a haircut to fugitives who had often been on the road for days or weeks, in addition to gathering information from informants across the city in order to anticipate the actions of the slave hunters who prowled the city.

All of this cost money, and Still was also responsible for raising that money and making sure the money was accounted for. Each expenditure was carefully recorded in his neat hand. Still’s work sometimes brought him face to face with the enemy—an arrogant slaveholder on the Delaware docks or a villainous slave catcher in a Philadelphia back alley—but most often his work found him, as he was that night when Freedman walked in, seated at his desk, writing.

“Good evening, sir,” Freedman’s guide said when they entered Still’s office. “Here is a man from the South that says he is hunting for his people, and he wants to make me believe he was born in Philadelphia.” Still looked at Freedman. “What were your parents’ names?” he asked. Freedman told him about his parents, his older brother Levin and his sisters. “Nineteen years ago, my brother died in Alabama,” he said, “and now I’ve bought my liberty and come back to hunt for my relations.”

Still asked him to repeat the names and inquired if there was anybody else Freedman could remember, peppering him with questions as though he did not believe what Freedman said and was hoping to catch him in some inconsistency. Then, apparently satisfied, he told his visitors he needed to finish preparing the mail and asked them to wait. When he returned, after nearly an hour, he said, “It will take some time to look over these papers, and this man may as well go home.” The guide rose to leave, and Freedman, anxious that these men were conspiring against him and seeing an opportunity to escape, rose as well. “I’ll go, too,” he said. “No, no—stay,” Still said. “I will do my best to find your friends.”

Once the guide left, Still sat next to Freedman and looked him directly in the face. “Suppose I should tell you that I am your brother?” he said, his voice now trembling. “My father’s name was Levin, and my mother’s name is Sidney, and they lost two boys named Levin and Peter, about the time you speak of. I have often heard my mother mourn about those two children, and I am sure you must be one of them.”

By the time Still came face to face with his long-lost brother, he had already committed himself to aiding fugitives from slavery. But he would later recall that the unexpected reunion inspired a new commitment to keeping detailed records of his work, in order to enable the reunions of other families torn apart by slavery and the flight to freedom.

This work became increasingly dangerous in the 1850s, after the passage of the Fugitive Slave Law, which strengthened the hand of slave catchers operating in Northern cities like Philadelphia. Despite the risk, Still felt that if the society could provide fugitives some possibility of “restoration of lost identities, and the reunion of severed relationships,” it would be worth it. Ultimately, he was able to preserve records about a substantial portion of the perhaps 1,000 fugitives he aided in his time at the Anti-Slavery Society.

A deeply personal part of that work was his effort to help his brother. After their remarkable meeting, the two traveled across the Delaware River to New Jersey, where most of the Still family lived. There, Peter (who eventually took the last name Still) was reunited with his mother, who was by then nearly 80. “O, Lord,” she cried upon seeing him, tears running down her cheeks. “How long have I prayed to see my two sons!”

Eventually, Still helped Peter free his wife and children, who remained in bondage in Alabama. After a failed attempt to help them escape north, Peter eventually raised enough money to purchase their freedom and bring them to the North—an effort aided by his brother’s extensive connections among wealthy abolitionists. Peter and his family settled in New Jersey, not far from his mother and many of his brothers and sisters.

Alongside his abolitionist work, Still pushed for the rights of Black people—not just freedom from slavery but the full rights of American citizenship. He fought for the desegregation of Philadelphia’s streetcars. He pushed for economic progress, including the right to hold the well-paying jobs that so often excluded Black Americans. He encouraged them to start businesses as the likeliest route to economic success. He himself became a prosperous coal dealer, and he called for others to follow in his footsteps. He also advocated for Black people to be granted the right to vote, and then worked to persuade Black voters to wield that right in a way that promoted the interests of their community.

Yet the question remains why a man who was once called the “father of the Underground Railroad” is so often overlooked today. In the more than 100 years since his death, Still has been marginalized, sometimes even forgotten, by histories of the movements to which he contributed so much. What accounts for this? Still was a seemingly ordinary man who did extraordinary things. This helps explain why we know far less about him than some of his better-known contemporaries.…

Still’s actions are easier to miss in part because when he told the stories of the Underground Railroad, he removed himself from the spotlight and placed it on the actions of fugitives from slavery themselves.

In 1872, Still published a monumental account of his work, The Underground Railroad, almost 800 pages recounting the stories of hundreds of fugitives he helped on their way north. For those looking to learn about Still’s actions, this book has sometimes proved frustrating; it can be difficult to find his hand at all. This was by design. Still understood, and wanted his readers to understand, that fugitive slaves were the engine of the Underground Railroad, that they were agents in their own liberation… Still’s work shows us that enslaved people were prepared to save themselves—they simply needed a hand. In this way, his life isn’t a story of the triumph of a heroic, lone individual. It is, rather, a story of community struggle and one man’s critical part in that struggle.

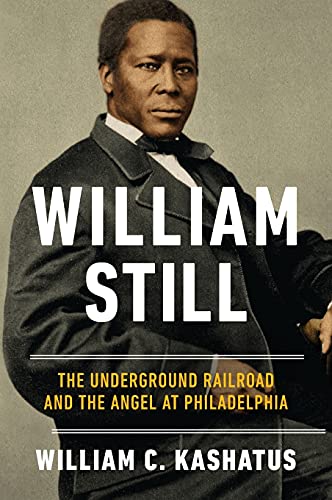

William Still: The Underground Railroad and the Angel at Philadelphia

Amazon Description

The first full-length biography of William Still, one of the most important leaders of the Underground Railroad.

William Still: The Underground Railroad and the Angel at Philadelphia is the first major biography of the free Black abolitionist William Still, who coordinated the Eastern Line of the Underground Railroad and was a pillar of the Railroad as a whole. Based in Philadelphia, Still built a reputation as a courageous leader, writer, philanthropist, and guide for fugitive enslaved people. This monumental work details Still’s life story beginning with his parents’ escape from bondage in the early nineteenth century and continuing through his youth and adulthood as one of the nation’s most important Underground Railroad agents and, later, as an early civil rights pioneer.

Still worked personally with Harriet Tubman, assisted the family of John Brown, helped Brown’s associates escape from Harper’s Ferry after their famous raid, and was a rival to Frederick Douglass among nationally prominent African American abolitionists. Still’s life story is told in the broader context of the anti-slavery movement, Philadelphia Quaker and free black history, and the generational conflict that occurred between Still and a younger group of free black activists led by Octavius Catto.

Unique to this book is an accessible and detailed database of the 995 fugitives Still helped escape from the South to the North and Canada between 1853 and 1861. The database contains twenty different fields―including name, age, gender, skin color, date of escape, place of origin, mode of transportation, and literacy―and serves as a valuable aid for scholars by offering the opportunity to find new information, and therefore a new perspective, on runaway enslaved people who escaped on the Eastern Line of the Underground Railroad. Based on Still’s own writings and a multivariate statistical analysis of the database of the runaways he assisted on their escape to freedom, the book challenges previously accepted interpretations of the Underground Railroad. The audience for William Still is a diverse one, including scholars and general readers interested in the history of the anti-slavery movement and the operation of the Underground Railroad, as well as genealogists tracing African American ancestors.

Amazon Description

A riveting collection of the hardships, hairbreadth escapes, and mortal struggles of enslaved people seeking freedom: These are the true stories of the Underground Railroad. Featuring a powerful introduction by Ta-Nehisi Coates

As a conductor for the Underground Railroad—the covert resistance network created to aid and protect slaves seeking freedom—William Still helped as many as eight hundred people escape enslavement. He also meticulously collected the letters, biographical sketches, arrival memos, and ransom notes of the escapees. The Underground Railroad Records is an archive of primary documents that trace the narrative arc of the greatest, most successful campaign of civil disobedience in American history.

This edition highlights the remarkable creativity, resilience, and determination demonstrated by those trying to subvert bondage. It is a timeless testament to the power we all have to challenge systems that oppress us.

Vigilance: The Life of William Still, Father of the Underground Railroad

The remarkable and inspiring story of William Still, an unknown abolitionist who dedicated his life to managing a critical section of the Underground Railroad in Philadelphia—the free state directly north of the Mason-Dixon Line—helping hundreds of people escape from slavery.

Born free in 1821 to two parents who had been enslaved, William Still was drawn to antislavery work from a young age. Hired as a clerk at the Anti-Slavery office in Philadelphia after teaching himself to read and write, he began directly assisting enslaved people who were crossing over from the South into freedom. Andrew Diemer captures the full range and accomplishments of Still’s life, from his resistance to Fugitive Slave Laws and his relationship with John Brown before the war, to his long career fighting for citizenship rights and desegregation until the early twentieth century.

Despite Still’s disappearance from history books, during his lifetime he was known as “the Father of the Underground Railroad.” Working alongside Harriet Tubman and others at the center of the struggle for Black freedom, Still helped to lay the groundwork for long-lasting activism in the Black community, insisting that the success of their efforts lay not in the work of a few charismatic leaders, but in the cultivation of extensive grassroots networks. Through meticulous research and engaging writing, Vigilance establishes William Still in his rightful place in American history as a major figure of the abolitionist movement.

Film: The Underground Railroad

“From Academy Award winner Barry Jenkins and based on the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel by Colson Whitehead, “The Underground Railroad” is a new series that chronicles Cora Randall’s desperate bid for freedom in the Antebellum South. After escaping a Georgia plantation for the rumored Underground Railroad, Cora discovers no mere metaphor, but an actual railroad beneath the Southern soil.”

The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead has 31,911 reviews on Amazon with a rating of 4.5.

Amazon Description

Winner of the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award, this #1 New York Times bestseller chronicles a young slave’s adventures as she makes a desperate bid for freedom in the antebellum South. The basis for the acclaimed original Amazon Prime Video series directed by Barry Jenkins.

Cora is a slave on a cotton plantation in Georgia. An outcast even among her fellow Africans, she is on the cusp of womanhood—where greater pain awaits. And so when Caesar, a slave who has recently arrived from Virginia, urges her to join him on the Underground Railroad, she seizes the opportunity and escapes with him.

In Colson Whitehead’s ingenious conception, the Underground Railroad is no mere metaphor: engineers and conductors operate a secret network of actual tracks and tunnels beneath the Southern soil. Cora embarks on a harrowing flight from one state to the next, encountering, like Gulliver, strange yet familiar iterations of her own world at each stop.

As Whitehead brilliantly re-creates the terrors of the antebellum era, he weaves in the saga of our nation, from the brutal abduction of Africans to the unfulfilled promises of the present day. The Underground Railroad is both the gripping tale of one woman’s will to escape the horrors of bondage—and a powerful meditation on the history we all share.

Documenting The Underground Railroad

Making a TV show about slavery could undo you. Unless the director steps up like this

Director Barry Jenkins brought in a mental health counselor to help his cast and crew navigate the challenging material of “The Underground Railroad,” which stars Thuso Mbedu.

Review: In ‘The Underground Railroad,’ an Oscar winner reimagines slavery from the inside out

The brutal reality of slavery, the fantastical storytelling of a Pulitzer Prize-winning author and the cinematic poetry of an Oscar-winning director meet in Amazon Prime Video’s “The Underground Railroad.”

Based on Colson Whitehead’s novel of the same name, the limited series, which premieres Friday, imagines a subterranean locomotive system that travels through a labyrinth of tunnels under the Southern United States, connecting runaway slaves to a network of abolitionists and safe houses on the way to freedom.

The 10-episode drama follows enslaved teenager Cora (Thuso Mbedu) and young man Caesar (Aaron Pierre) as they flee a cruel Georgia plantation only to discover that “free” white America has found plenty of creative ways outside of slavery to demonize, oppress, and imprison Black folks. Cora and Caesar stumble into a fresh hell with each new “chapter” in the tale, many named for the states in which they’re set.

Join Gary Kent as he pays a visit to another world, another age, a nineteenth-century New England village that has been rebuilt. He talks about why a town like this embodied freedom–as a key destination for the Underground Railroad. Follow in their footsteps as we discover how people took a voyage to freedom.

Dawn of Day: Stories from the Underground Railroad

Dawn of Day is a historical documentary about the Underground Railroad in Kansas that brings to light Wabaunsee County’s unsung heroes who traversed one of the most turbulent times in our nation’s history. Faith, family, and politics united a community of neighbors who lived and died to ensure Kansas was a free state. Richard Pitts, director of the Wonder Workshop in Manhattan, Kansas, narrates the film and interviews educators, historians, and descendants of abolitionists whose shared heritage lives on in the freedom we enjoy today.

Note: The earlier Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 was a Federal law written to enforce Article 4, Section 2, Clause 3 of the United States Constitution which required the return of escaped slaves. By 1843, several hundred enslaved people a year escaped to the North, making slavery an unstable institution in the border states.

Neenah Payne writes for Activist Post and Natural Blaze

Become a Patron!

Or support us at SubscribeStar

Donate cryptocurrency HERE

Subscribe to Activist Post for truth, peace, and freedom news. Follow us on SoMee, Telegram, HIVE, Flote, Minds, MeWe, Twitter, Gab, What Really Happened and GETTR.

Provide, Protect and Profit from what’s coming! Get a free issue of Counter Markets today.

Be the first to comment on "The Remarkable Underground Railroad"