The lockdowns enacted around the world in 2020 serve as a visceral reminder of what happens when economic freedom is undermined.

If a threat is perceived to be high enough, governments consider it their duty to act as they see fit—no matter the possible negative future consequences. According to the World Bank, the number of people in extreme poverty is projected to increase by up to 150 million by 2021, while the United Nations projects the ranks of the poor could swell by 240 million to 490 million this year.

Fact: Lockdowns and other government restrictions are causing extreme poverty to surge globally.

This will result in more empty bellies, more malnutrition, more disease, and – tragically – way more deaths. pic.twitter.com/vAb8fpsajj

— Jon Miltimore (@miltimore79) November 19, 2020

The results of limits on individual liberty—often felt most harshly by poorer people—should serve as a costly lesson for central planners and policy makers. The devastation of ill-considered policy has been felt around the world but is even starker in developing economies, such as South Africa.

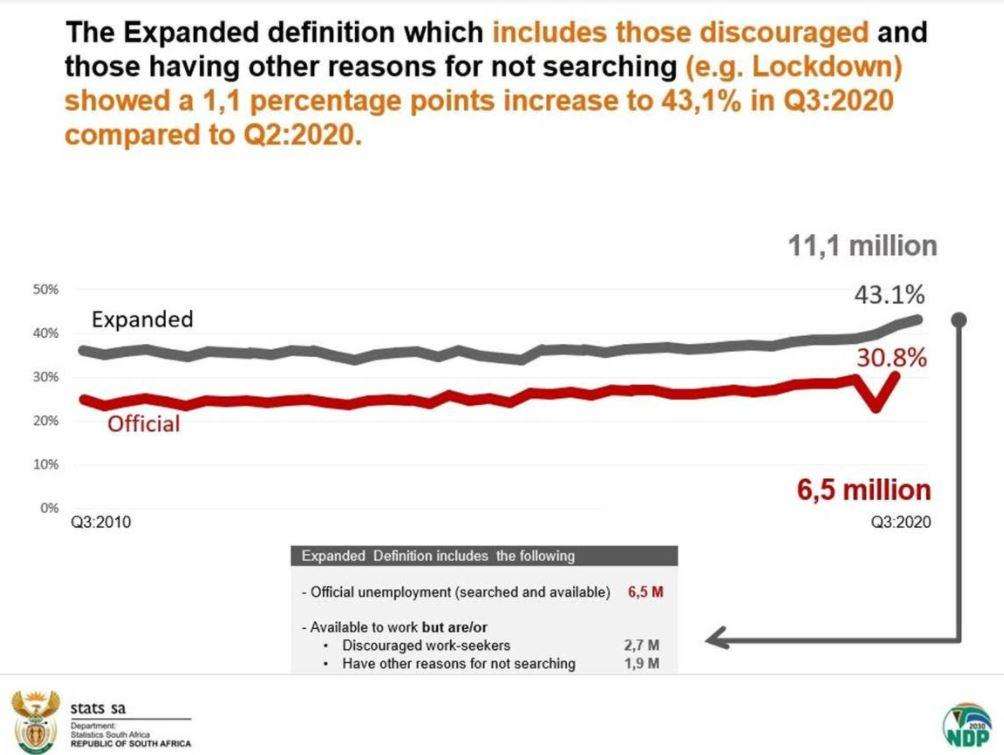

As of Q3 2020, South Africa’s unemployment rate stands at 43.1 percent (using the expanded definition, which includes discouraged job seekers who have stopped looking for work). Youth unemployment is now 74 percent. With its history of enforced racial separation and state-increased inequalities, it was imperative that the country embrace the awesome power of economic freedom from 1994 onwards. There have been periods of progress, but not to a greatly sustained extent. That there are now more people who are unemployed than earning a paycheck every month is concrete evidence that South Africa has not adopted the correct policies (with the latest example being the country’s hard lockdown).

In more developed economies, there is a higher chance that those who lost their jobs earlier this year will return to employment once lockdowns are lifted. However, in South Africa, the data are telling a different story—again reinforcing the idea that government should have acted with more caution before implementing a hard lockdown. Some 2.2 million jobs were lost during the second quarter of this year. Of those lost jobs, 539,000 returned in the third quarter. This means there were still 1.7 million fewer people working in the third quarter, compared to a year before. Viewed another way, just 37 out of every 100 South Africans of working age are employed.

A lower labor absorption rate indicates that businesses are simply not hiring. Numerous factors have contributed to this in South Africa, most notably affirmative action policies, unreliable power supply, a national minimum wage that prices out people from work, employment-discouraging hiring and firing legislation, and a general lack of confidence in the country’s business environment.

With the implementation of a hard lockdown, the government assumed the position of dictating which businesses were “essential” and which were not. Those businesses that have managed to survive the ravages of this year, will be exceedingly cautious before hiring again.

In 2000, South Africa was ranked 58th on the Fraser Institute’s Economic Freedom of the World Index (EFW). In this year’s edition, the country sits at 90th, out of 162 countries. The data captured in the EFW help to illustrate that, in countries that adopt economic freedom to a greater extent, citizens’ quality of life is on average much higher than in countries that restrict freedom.

The slide from 58th to 90th is reflected in the reality on the ground—ever-increasing unemployment, decreasing capital formation and investment, and an increasing number of people seeking to live and work elsewhere, shows what happens when a government implements policies that undermine freedom. At this point, South Africa’s private sector employs only around 8 million people—these 8 million now bear the pressure to create most of the country’s economic value, while supporting various welfare programs. The situation is untenable.

The COVID-19 hard lockdown has served to highlight and intensify South Africa’s structural economic and labor market weaknesses. On 19 November, the South African Reserve Bank forecast that the economy would contract by 8 percent this year. The government is quickly running out of fiscal runway to supply support. The debt-to-GDP ratio is projected to exceed 92 percent in 2023-24; to address this issue, the government aims to freeze public-sector wages for the next 3 years. All signs point to an escalating conflict between government and unions on this particular issue. That the ever-increasing public-sector wage bill is exerting so much pressure on the state’s finances indicates the grave extent to which the government undertook to be the main driver of economic growth years ago.

Become an Activist Post Patron for $1 per month at Patreon.

Heading out of COVID-19, it is imperative that the South African government heeds the lessons of lockdowns, and look to the policy recommendations and changes that indices such as the EFW provide. Lessing the iron grip of trade unions, opening the electricity market to competition, and abandoning plans that will increase the power of the state—such as expropriation of property without compensation, monopolizing all healthcare in the hands of the state through the National Health Insurance, and implementing prescribed assets to compel pension funds to invest in state-owned companies—is the truly radical change in policy direction that the country needs.

“State-led growth” is not the answer for the country. Even if the government had more fiscal room to play with, when the government controls and dictates the allocation of capital, the results are inefficiency and bloat. It is not the state’s duty to pool all wealth in the country, and then presume that it can redistribute people into prosperity. Only through increasing the ease of doing business (from the corporate level to the street corner) will government truly act in the best interests of the people.

Once the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) is implemented in 2021, South Africa could be one of the main hubs of innovation, employment, and prosperity in the Southern African region. But to dovetail with the massive potential of the AfCFTA, South Africans need more economic freedom than ever before.

More than 11 million people are now unemployed. One cannot make substantial progress in addressing such devastation without adopting radical policies—policies informed by economic freedom. For the politicians and bureaucrats, this moment demands that they shelve their hubris and belief that they know best what will work, hold back their fears that people will abuse freedom if they have more thereof, and trust in South Africans’ potential to bake their own wealth pies.

Source: FEE.org

Chris Hattingh is Project Manager at the Free Market Foundation. He has an MPhil in Business Ethics from Stellenbosch University. He is the author of published articles on consumer rights, economic freedom, inequality and individual freedom.

Subscribe to Activist Post for truth, peace, and freedom news. Send resources to the front lines of peace and freedom HERE! Follow us on SoMee, HIVE, Parler, Flote, Minds, MeWe and Twitter.

Provide, Protect and Profit from what’s coming! Get a free issue of Counter Markets today.

Be the first to comment on "Lockdowns Have Pushed South Africa’s Economy to the Brink"