For those unfamiliar with the full goals of The Singularity Movement, it is valuable to visit the website 2045 — the theoretical date when computer intelligence surpasses that of humanity, thus establishing a new form of social and economic contract.

Just a short while ago — more or less yesterday — a “Rise of the Robots” scenario was being debated for its potential Utopian and Dystopian outcomes. Then the movie Avatar supplanted Terminator to reflect an entirely new possibility.

It didn’t take very long: the Avatar has now arrived, and scientists are beginning to study the effects of how virtual reality can impact one’s perception of themselves and those around them in the real world. Early conclusions are troubling.

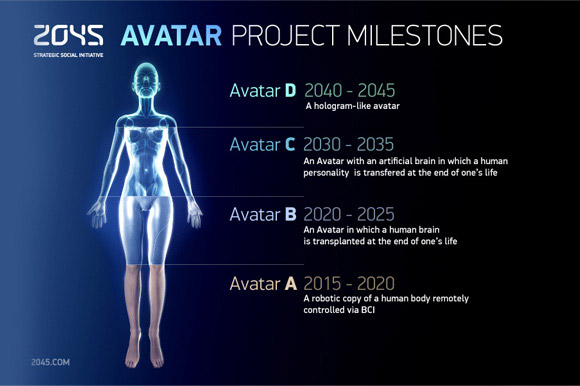

The Avatar Project has very clear milestones as documented on the 2045 website. They are as follows:

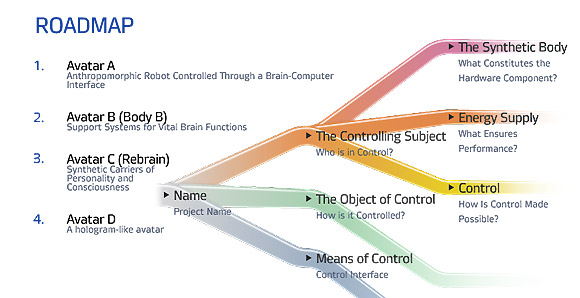

A roadmap also illustrates the progression:

New Scientist announced in July of last year a significant step in merging reality with virtual reality. The model avatar took the body of a four-year-old child. It’s was a tentative step, as would be the case with any four-year-old, but suggested that the mind can begin to merge with any body it wishes inside the digital landscape:

Mel Slater of the University of Barcelona in Spain and colleagues put 30 people in a virtual reality (VR) environment in the body of a 4-year-old child or a scaled-down adult the same height as the child. The virtual body, which moved in sync with movements of the real body, could be viewed from a first-person perspective and in a mirror in the VR environment.….

Prior research by Slater’s team shows that when a person acquires a body type they have never experienced, social and cultural expectations often influence how they relate to the new body.

Studies are underway to take into account the two-way nature of this information/perception transfer.

Concurrently, it appears that similar to one’s preconceptions in the real world impacting the virtual experience, actions taken in the virtual world are being shown to impact the primary reality:

Things we experience in a virtual landscape can also have profound effects on our behaviour in the real world: in a separate study by researchers at Stanford University in California, giving people superhero powers in a virtual environment made them behave in a more helpful manner in real life.

The researchers say that brain imaging studies would help them to understand the reorganisation that occurs when assimilating a new body. The motivation springs from a project looking at how to embody people in child-sized robots. “We thought we ought to look at the consequences of that first,” says Slater.

A more recent study published in the highest ranked empirical journal in psychology – Psychological Science – drew similar conclusions about how the virtual world can impact the real, and gives further insight into how easily a “player” can become programmed. This would seem to lend credence to those who assert that violent video games, for example, can lead to aberrant behavior that models the role one has assumed in the game. As the study illustrates, one does not necessarily need to identify with the character, which would rule out the argument that people with violent tendencies who play violent video games are prone to violent action later. With the added immersion of virtual reality, this potential is likely amplified.

A more recent study published in the highest ranked empirical journal in psychology – Psychological Science – drew similar conclusions about how the virtual world can impact the real, and gives further insight into how easily a “player” can become programmed. This would seem to lend credence to those who assert that violent video games, for example, can lead to aberrant behavior that models the role one has assumed in the game. As the study illustrates, one does not necessarily need to identify with the character, which would rule out the argument that people with violent tendencies who play violent video games are prone to violent action later. With the added immersion of virtual reality, this potential is likely amplified.

“Our results indicate that just five minutes of role-play in virtual environments as either a hero or villain can easily cause people to reward or punish anonymous strangers,” says lead researcher Gunwoo Yoon of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

As Yoon and co-author Patrick Vargas note, virtual environments afford people the opportunity to take on identities and experience circumstances that they otherwise can’t in real life, providing “a vehicle for observation, imitation, and modeling.”

They wondered whether these virtual experiences — specifically, the experiences of taking on heroic or villainous avatars — might carry over into everyday behavior.

The researchers recruited 194 undergraduates to participate in two supposedly unrelated studies. The participants were randomly assigned to play as Superman (a heroic avatar), Voldemort (a villainous avatar), or a circle (a neutral avatar). They played a game for 5 minutes in which they, as their avatars, were tasked with fighting enemies. Then, in a presumably unrelated study, they participated in a blind taste test. They were asked to taste and then give either chocolate or chili sauce to a future participant. They were told to pour the chosen food item into a plastic dish and that the future participant would consume all of the food provided.

The results were revealing: Participants who played as Superman poured, on average, nearly twice as much chocolate as chili sauce for the “future participant.” And they poured significantly more chocolate than those who played as either of the other avatars.

Participants who played as Voldemort, on the other hand, poured out nearly twice as much of the spicy chili sauce than they did chocolate, and they poured significantly more chili sauce compared to the other participants.

A second experiment with 125 undergraduates confirmed these findings and showed that actually playing as an avatar yielded stronger effects on subsequent behavior than just watching someone else play as the avatar.

Interestingly, the degree to which participants actually identified with their avatar didn’t seem to play a role:

“These behaviors occur despite modest, equivalent levels of self-reported identification with heroic and villainous avatars, alike,” Yoon and Vargas note. “People are prone to be unaware of the influence of their virtual representations on their behavioral responses.”

The researchers hypothesize that that arousal, the degree to which participants are ‘keyed into’ the game, might be an important factor driving the behavioral effects they observed.

The findings, though preliminary, may have implications for social behavior, the researchers argue:

“In virtual environments, people can freely choose avatars that allow them to opt into or opt out of a certain entity, group, or situation,” says Yoon. “Consumers and practitioners should remember that powerful imitative effects can occur when people put on virtual masks.” (Source) [emphasis added]

These studies are being done as Ray Kurzweil’s vision to merge our bodies and brains with cloud computing via DNA nanobots is coming closer to fruition. We would do well to consider the intended and unintended consequences much more closely while the divide between real and virtual still remains perceptible.

Related:

7 Future Methods of Mind Control

Recently by Nicholas West:

- Obama Doubles Down on BRAIN Project and Military Mind Control

- Facebook Interested in Solar Drones For Global Internet

- Dragonfly: World’s Smallest Autonomous Drone Takes Flight

Updated 3/9/2014

Nicholas West writes for ActivistPost.com. This article can be freely republished with author attribution and source link.

Be the first to comment on "Avatars and Their Behavioral Effect on Reality"